6.4.1 Snapshot of key findings

6.4.2 Exposure and vulnerabilities

Vulnerable people and places

In all communities, some groups of people are more vulnerable than others. They include:

- households with one or more disabled person

- households with elderly people (over 60 years old in the PNG context)

- households headed by a woman; those with particularly low cash incomes

- households where one or more person has migrated to or within the province.

There are also locations where most people suffer multiple disadvantages and are particularly vulnerable to external shocks, such as a pandemic, drought, earthquake or tsunami. Most (94%) of these people live in rural locations (Gibson et al 2005). Disadvantage manifests in different ways, including some or all of the following:

- high infant mortality

- high under-five child mortality

- high maternal or neo-maternal death rate

- short life expectancy for adults who survive childhood

- low proportion of children who attend school

- low proportion of children who complete high school

- very low proportion of young adults who complete tertiary education

- low literacy rates for all age groups

- poor access to health facilities

- low cash income

- poor market access

- limited political influence.

From the early-1970s to the mid-2000s, five studies have been conducted on relative disadvantage (poverty) in PNG, of which the 2004 study by National Economic and Fiscal Commission on development indicators for least-developed districts was not formally published (Wilson 1975, de Albuquerque & D’Sa 1986, Hanson et al 2001, World Bank 2004). The 2004 World Bank poverty assessment was an update of an extensive 1996 poverty survey (Gibson & Rozelle 2003). Each of these studies has some limitations. However, when examined together there is significant consistency and, despite the different parameters considered and the different time periods, they identify the same broad pattern. Table 6.6 lists 20 districts identified as being particularly disadvantaged in 3–5 of these studies. If a district appears in most of the five studies, which were done independently and using different methods, it suggests that:

- it is highly likely that many (or even most) people in those districts suffer multiple disadvantages

- the position of most people in those districts has not changed much over 40 years relative to the situation of people in other districts.

The most disadvantaged districts in PNG are Telefomin, Vanimo-Green River, Middle Ramu, Rai Coast, Goilala, Koroba-Lake Kopiago and Jimi. These seven districts were identified in all five studies conducted over a 40-year period. Other districts that were identified in four of the five studies are Nuku, Aitape-Lumi, Menyamya, Obura-Wonenara, Usino-Bundi and Kandep. A further seven districts were identified in three of the five studies.

The most disadvantaged communities are located:

- between the coast and the main highland valleys (on the edge of the densely populated highland valleys)

- in the intermediate altitude zone

- in inland lowland locations.

The most disadvantaged places are on the New Guinea mainland, not on smaller islands, except for Pomio District in East New Britain province.

Three districts, Obura-Wonenara (Eastern Highlands Province), Kerema (Gulf province) and Karimui-Nomane (Simbu province) were found to be disadvantaged in some but not all of the five studies. This is because these districts contain areas of extreme disadvantage as well as more advantaged areas. This can be misleading because all three of these districts have significant pockets of extremely disadvantaged people.

A summary of the outcome of studies on rural poverty in PNG is given by Allen (2009:S6.10). Other analyses on rural poverty include Allen et al (2005), Gibson and Rozelle (2003) and Gibson et al (2005). A map in Hanson et al (2001:300) indicates where the most disadvantaged people live, with data presented in finer detail (land used for agricultural production) than using district boundaries.

Table 6.6 The most disadvantaged districts in PNG, as identified in five studies of poverty

| Districta | Province | No. of studiesb |

|---|

| Telefomin | West Sepikc | 5 |

| Vanimo-Green River | West Sepik | 5 |

| Middle Ramu | Madang | 5 |

| Rai Coast | Madang | 5 |

| Goilala | Central | 5 |

| Koroba-Lake Kopiago | Hela | 5 |

| Jimi | Jiwaka | 5 |

| Nuku | West Sepik | 4 |

| Aitape-Lumi | West Sepik | 4 |

| Menyamya | Morobe | 4 |

| Obura-Wonenara | Eastern Highlands | 4 |

| Usino-Bundi | Madang | 4 |

| Kandep | Enga | 4 |

| Ambunti-Dreikikir | East Sepik | 3 |

| Kerema | Gulf | 3 |

| Kabwum | Morobe | 3 |

| Pomio | East New Britain | 3 |

| Lagaip-Porgera | Enga | 3 |

| Nipa-Kububu | Southern Highlands | 3 |

| North Fly | Western | 3 |

Notes:

- The districts are ordered from most to least disadvantaged (from an unpublished 2004 study by National Economic and Fiscal Commission). There are currently 85 rural districts in PNG, plus Lae Urban district and National Capital District (Port Moresby). District names and boundaries have changed over time.

- The column ‘Number of studies’ refers to the number of times that each district was identified as being in the bottom 20 districts in each study. For example, Telefomin was reported as being one of the most disadvantaged districts in all five studies, and North Fly was identified in three of the five studies.

- West Sepik Province is also known as Sandaun.

Existing long-term issues

There are a number of major issues impacting on food security, human nutrition and human health in PNG. While not especially amplified by the COVID-19 state of emergency and related lockdowns at this stage, these issues have significant implications for the lives of many Papua New Guineans now and in coming decades, particularly in rural locations.

Rapid population growth

The physical environment in much of PNG is not suitable for productive agriculture. Less than one-third of the land area is used for agricultural production because of environmental constraints (extremely low soil fertility, long-term inundation, steep slope and very high altitude) (Allen & Bourke 2009:Table 1.2.2). The high rate of population increase is putting pressure on farming land in certain environments (as well as on education and health resources). Pressure on land is greatest on small islands and in the central highlands (agroecological zones 1, 7, 8 and 9 in Table 6.2). On many small islands, even food crops that are more tolerant of low soil fertility, such as sweetpotato, triploid bananas and cassava, give low yields and the traditional staples of taro, yam and diploid bananas barely yield any food. The introduction and widespread adoption of sweetpotato in the highlands about 350 years ago resulted in the large gains in productivity. However, more intensive land use and declining soil fertility is placing pressure on food supply in the highlands in the absence of further novel species to introduce.

The adoption of novel food crops, mostly from the Americas, over the past 150 years in much of the lowlands and intermediate altitude zones (agroecological zones 2, 3, 5 and 6 in Table 6.2) has allowed the increased population to be fed, sometimes with reduced labour inputs as the novel species can be grown under more intensive land use conditions. The change in the mix of food crop species continues in many of these locations, particularly with the increased cultivation of sweetpotato, cassava and triploid bananas, but increasing pressure on land will eventually negate those gains in the medium to long term.

Climate change

This issue was not highlighted by the COVID-19 crisis and is not addressed in detail here. It is sufficient to note that:

- the rate of temperature increase in the PNG highlands is occurring at a much higher rate than the global average (as it is in other tropical highland locations globally)

- rising sea levels are already impacting on agricultural production on some atolls and other small islands

- rainfall patterns are changing in many locations in the nation, with increased rainfall and more intensive rainfall events in many locations.

These changes have significant implications for agricultural production in coming decades.

High rates of child undernourishment

State-of-emergency conditions may impact upon children in rural areas who have less access to foods higher in protein and oils/fats, and children in urban and peri-urban settings who have less access to vegetables and food with a higher protein content. However, even in the absence of the state of emergency, child malnutrition remains a significant issue in PNG and needs greater attention, including greater efforts to educate the population on basic human nutrition needs.

Issues amplified by the COVID-19 state of emergency

Inadequate health services

The health service in PNG is already operating beyond its capacity to cope well (Mola 2020). Impressive preparations for the COVID-19 pandemic were made in some provincial hospitals. The planning done by the national Department of Health with technical support from the World Health Organization and financial support from overseas sources has almost certainly strengthened the health system. However, in the event of a large-scale outbreak, as has occurred in parts of North America, South America and Europe, PNG’s health system would be totally overwhelmed. The assessment interviews and 27 case study stories collected by non-government organisations, together with social media posts, identified examples of COVID-19 response measures having adverse consequences for people’s health through the closure of health facilities, roadblocks hindering access to health care and refusal of health staff to provide treatment. However, it is not possible to quantify these in the absence of adequate demographic and health baselines and recent surveys.

Gender inequality

A recent report concluded that:

Rural women play multiple roles simultaneously, including managing triple responsibilities in their workplaces, households and communities. They take on the primary responsibility to ensure that the nutritional, childcare and health needs of their families are fulfilled, in addition to the community, social, and cultural roles they are expected to perform. Given these multiple roles and duties, rural women lack the time to participate in other opportunities that could potentially help to enhance their knowledge, skills, and self-esteem. Women disproportionately bear the consequences of alcoholism and addiction of household members as compared to men, as well as facing higher rates of domestic violence (FAO 2019).

With the COVID-19 crisis, the lives of many PNG women, particularly in the highlands, have been made more difficult. Case studies of individual women, particularly those in Jiwaka Province, highlight the loss of cash income and heightened exposure to different forms of violence, exacerbated by the diversion of police resources to other COVID-19 crisis response tasks. State-of-emergency conditions have made an already difficult situation even worse.

Dependence on informal food marketing

Closure of food markets, provincial borders and inter-island travel highlighted a number of key issues on the role of marketed food in the informal economy:

- Marketing fresh food, fish, live animals and meat is a significant part of many rural people’s livelihoods strategy, particularly women.

- The shift in production and marketing from export commodities to food and other items for the domestic market over the past 30 years is a significant change in many locations.

- There is significant long-distance trade in food, particular across ecological zones, for example from locations with contrasting temperature (altitude) and rainfall patterns.

- There are strong economic links between urban consumers and rural producers in many locations, with mutual dependence.

Urban influence

The needs of urban populations in PNG strongly influence aspects of food security and related policy areas. This is reflected in the emphasis given to the continuity of supply and the price of rice and vegetables in urban areas during the COVID-19 state of emergency, relative to issues affecting rural villagers like loss of cash incomes. Urban-based informants commonly stated that rural villagers were not impacted greatly or at all by the lockdowns. Likewise, Inamara (2020) reported that lockdowns have not presented ‘real issues with food security for rural farmers’. Conversely, a development non-government organisation–based informant in a remote location stated: ‘We continue to see a huge divide created in PNG. COVID-19 is another example of this. All the effort and energy goes into the same places. And the remote places get pushed further back.’

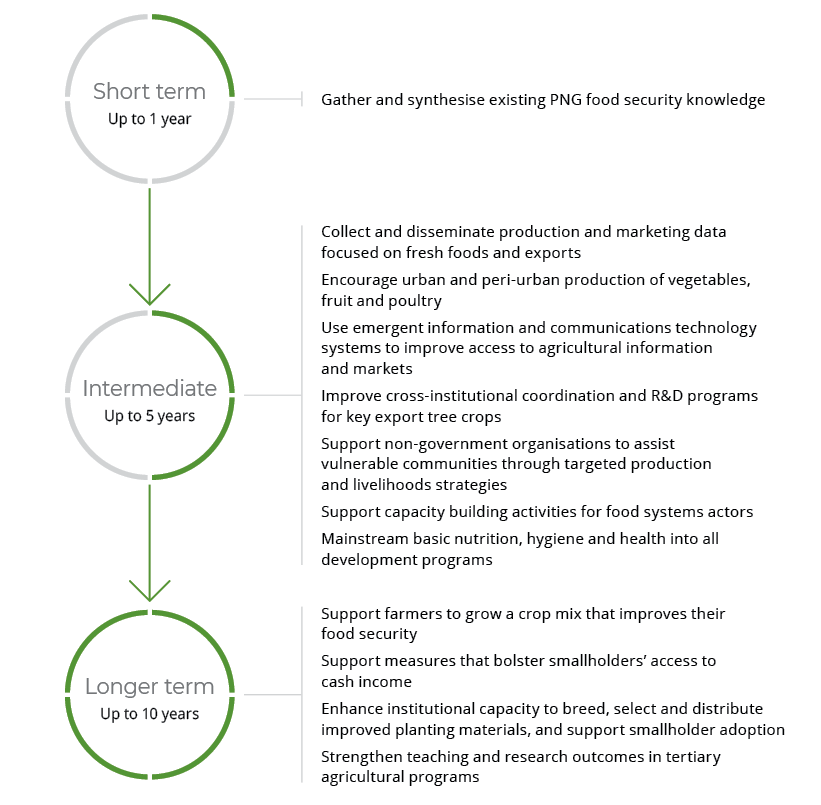

Food security policy, development and research

Inadequate data

There is a dearth of recent high-quality data on many aspects of agriculture, food consumption and marketing. This is particularly acute for many aspects of food production and marketing, but it is also the situation for many major and minor export crops. Comprehensive statistical data were gathered for the book Food and Agriculture in Papua New Guinea (Bourke & Harwood 2009) and those data are on the web as Excel tables. However, the data runs stop in 2006 and 2007 and there have been a number of significant changes in the agricultural economy since then.

Data on the prices of the staple food crops is a particularly important parameter. These are an excellent indicator of changes in supply as many rural producers start to purchase fresh food when their subsistence supply is inadequate and prices increase significantly. Prices of a number of key food crops are recorded in eight urban centres as part of the datasets used to calculate the Consumer Price Index. However, there are numerous gaps in these data and particularly high variation in the prices recorded because of inadequate sample size. The price data of fresh food is eventually published, albeit with many gaps, but this does not occur until well after price data can be used as an indicator of events in the economy, such as, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the closure of fresh food markets. It is possible to obtain price data from the National Statistical Office in Port Moresby, but this requires much dedication.

For fresh food, fish and live animals, data are need on location of production, volume being sold, most aspects of market chains, food distribution networks, demand in urban and rural locations for different commodities, market prices and the volumes being sold through fresh food markets and in other venues.

Planting material shortages

The lack of planting material of suitable food crop varieties was highlighted by many informants. Crops mentioned included sweetpotato, corn (maize), common bean, temperate climate vegetables and fruit trees.

Institutional capacity

Public sector agricultural institutions in PNG have limited capacity. Processes tend to be slow and can result in procedural shortcuts. Significant gaps in agricultural research were noted by some key informants, with an agricultural development expert remarking that research ‘is not targeting the farming communities’.

A number of the universities provide training in aspects of agriculture, including University of Technology, Lae; University of Natural Resources and Environment, Vudal and Popondetta campuses; University of Goroka; and University of PNG. These institutions conduct only limited research on agricultural issues, partly due to lack of funds. Most students have no experience of field trips or work placements.

International and local non-government organisations have innovative programs supporting rural villagers with food production and marketing, as well as broader initiatives with particular emphasis on women. Examples in the case study stories from local non-government organisations include eDidiman in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, HELP Resources, Wewak and Voice for Change, Jiwaka Province.

Potentially maladaptive responses to the COVID-19 crisis

Self-sufficiency in food production

As Manning (2001) noted in a paper 20 years ago, food security is not the same as food self-sufficiency. He concluded:

There are benefits to be gained from trade and therefore we should not be aiming for self-sufficiency in food production. A well-managed economy and well-run government will allow the country to react to temporary setbacks while providing the framework for long-term development.

Access to imported food, mainly rice, enhances household food security, particularly when subsistence food supplies are scarce. This applies at the household and local level, but also at a regional and national level during major climatic extremes. This was illustrated most clearly in major food shortages in 1997–98 and again in 2015–16 (Allen & Bourke 2001, Whitecross & Franklin 2001, Kanua et al 2016).

The need for all or much of the rice consumed in PNG to be produced within the country is often stated as one way of increasing food security. It is more important for farmers to grow crops for domestic or overseas markets that grow well in the local environment and give high returns on their labour inputs. The latter is a key determinant of farm decision-making in PNG (Bourke & Harwood 2009:S5.20). The low returns on labour inputs in growing rice and other grains explain why there is a long history of failure to develop significant domestic rice production, despite the high level of effort over the past 100 years, particularly from the early 1950s to the late 1970s (Bourke et al 2009:S2.5).

Long-term storage of processed foods

It is commonly stated that, if villagers processed and stored food, these could be consumed when subsistence food was inadequate. This proposition ignores several critical factors:

- Food shortages occur irregularly and often many years apart. For example, if villagers stored processed food after the 1997 drought and food shortages, they may not have experienced another significant food shortage until the 2015 drought.

- It is not possible to store food post-harvest for extended periods under village conditions, given the high temperatures and humidity and attacks from insects and rodents.

- Cultural norms mean that it is not possible to store food in many PNG societies. When others in the community are short of food, people are obliged to share their stored food.

6.4.3 Impacts

The greatest impact of the COVID-19 crisis on food security has been on the sale of fresh food due to the closure of fresh food and fish markets, with particular implications for female sellers, urban consumers and others in the local communities. The impacts of the state of emergency on rural villagers and urban dwellers are now described.

Disruptions to food markets

During the state of emergency, fresh food could not be transported across provincial boundaries within the highlands, from the highlands to Lae and Madang, or from Gulf and Central provinces into Port Moresby. Police roadblocks stopped the transport of food and the movement of people more generally across provincial borders, into towns and between islands. When the lockdown started in late March 2020, all urban and some rural fresh food markets were closed. There was a prohibition on the sale of cooked food, fish, meat and live chickens in some urban markets (FAO 2020c). Many villagers could not sell their food, with significant losses to women’s incomes in particular.

The lockdown primarily focused on larger urban areas, and some smaller rural markets have continued to operate without significant disruption. For example, although the markets in Wewak town were closed, 35 other fresh food markets in the broader Wewak district continued to function. In West New Britain, social distancing of vendors was enforced in the main market that had reopened in Kimbe, the provincial capital, but not in numerous smaller rural markets.

Urban fresh food markets reopened at an uneven pace. Some reopened around mid-April 2020 (for example, Lae), but with fewer vendors allowed in order to maintain social distancing between them. Others were still closed in early May (for example, Kokopo, Kiunga, Goroka, Taro, Mt Hagen, Buka) (FAO 2020a). Most but not all markets (for example, Mt Hagen) had reopened by early July, with social distancing enforced in only some.

Curfews applied to some markets dented vendor incomes, especially the loss of sales from after-work foot traffic. In the Wewak area, the lockdown significantly impacted about 2,500 vendors (Kabilo 2020). These findings concur with the income impacts on women selling in the Caltex Market in Wewak, East Sepik Province (Table 6.7), and more generally with the case study stories of women selling fresh food and fish during and post lockdown.

Table 6.7 Impact of COVID-19 state of emergency on vendor’s daily takings at Caltex market, Wewak, East Sepik Province

| Type of vendor | Daily takings before COVID-19 restrictions | Daily takings during COVID-19 restrictions | Predicted daily takings after COVID-19 restrictions are relaxed |

|---|

| Garden food producers/wholesalers | K200 plus | Nil – K30 | K100–140 |

| Garden food resellers | K150 plus | Nil | K50–60 |

| Store goods resellers | K100 plus | Nil | K40–50 |

| Betel nut wholesaler | K200 plus | Nil | K100–120 |

| Betel nut reseller | K160 plus | Nil | K50–60 |

| Fish sellers | K250 plus | Nil | K100–150 |

| Cooked food sellers | K500 plus | Nil | K250–300 |

| Home sewn clothes sellers | K300 plus | Nil | K70–90 |

| Irregular sellers | K100 plus | Nil | K50–70 |

Source: Evangeline Kaima, Wewak

Increased prices in fresh food markets and disruptions to long-distance movement of fresh food

The price of fresh food rose in most urban centres in PNG due to fewer vendors and lower volumes of fresh food for sale. An informant reported that, in early April: ‘The price of fresh produce has increased quite steeply in Port Moresby due to lack of supply’. An informal survey of prices in Lae for 44 types of fresh food and stimulants (for example, betel nut) indicate that more than half increased in price during and post lockdown (Table 6.8). Most came from the highlands, but some were grown closer to Lae. People selling green vegetables at newly established roadside markets in Port Moresby sold them at K5 per bundle, up from the normal market price of K1–2 per bundle (FAO 2020a). Informants and the case study stories reported many other examples of price increases at other locations.

Table 6.8 Price of fresh produce in Lae before and since COVID-19 lockdowns (January–June 2020)

| Cropa | Price before lockdownb | Price since lockdown | Notes |

|---|

| Staples |

| Banana, cooking | K2 for 12 | K2 for 6 | less volume |

| Cassava (tapiok) | 50 toea – K1 each | No change | |

| Sweetpotato | K5 for 5–6 large | K5 for 3–4 large | less volume |

| Taro tru (Colocasia) | K10 for 10 corms | K10 for 6 corms | less volume |

| Taro kongkong (Xanthosoma) | K1 for 3 cormels | No change | |

| Yam, African | K1 for 3 tubers | No change | |

| Sugarcane | K1 for a long one | No change | |

| Sago | K5 for large container | K7 for large container | less volume |

| Vegetables |

| Aibika | K1 for 5–6 leaves | K1 for 3–4 leaves | less volume |

| Amaranthus spp (aupa) | K1 for large bunch | No change | |

| Bean, long (snake) | K1 for 10 beans | K1 for 5–6 beans | less volume |

| Broccoli | K3 for large one | K5 for large one | less volume |

| Cabbage, round | K3 for large one | K4 for large one | less volume |

| Capsicum | K1 for 5–6 | K1 for 3–4 | less volume |

| Carrot | K1 for 5–6 | K1 for 3–4 | less volume |

| Choko tips | K1 for large bundle | K1 for small bundle | less volume |

| Corn | K2 for 5–6 | No change | |

| Cucumber | K1 for 5–6 | K1 for three | less volume |

| Eggplant | K1 for large bundle | No change | no supply issue |

| Ferns | K1 for large bundle | K1 for small bundle | less volume |

| Garlic | K1 per clove | No change | |

| Ginger | K1 for large root | No change | |

| Highland pitpit | K2 for large bundle | K2 for small bundle | less volume |

| Lettuce | K1 for one | No change | |

| Onion | K1 for large bulb | No change | |

| Onion, spring; shallots | K1 for bundle | No change | |

| Peanuts | K1 for bundle | No change | |

| Potato | K2 for 6–8 tubers | K2 for 4 tubers | less volume |

| Pumpkin, fruit | K1 for small pumpkin | K2 for small pumpkin | less volume |

| Pumpkin, tips | K1 for large bundle | K1 for small bundle | less volume |

| Tomato | K1 for 3–4 | K1 for one | less volume |

| Watercress | K1 for large bundle | K1 for small bundle | less volume |

| Fruit and nuts |

| Avocado | K1 for one | No change | |

| Banana, ripe | K2 for small bundle | No change | |

| Guava | K1 for bundle | No change | |

| Lemon | K1 for bundle | No change | |

| Mandarin | 50 toea for one | K1 for one | less volume |

| Orange | K1 for large one | No change | |

| Pawpaw | K4 for large one | No change | less volume |

| Passionfruit | K1 for five | K1 for three | less volume |

| Pineapple | K2 for small one | K3 for small fruit | less volume |

| Karuka nuts | K1 for bunch | No change | |

| Narcotics |

| Betel nut, highlands (kavivi) | 50 toea for small one | K1 for small one | less volume |

| Tobacco | K1 for large leaf | No change | |

Notes:

- Bourke & Harwood (2009:xiv–xviii)

- K = PNG kina (currency); 100 toea = K1.

Source: Lae resident and regular market goer

There was a marked decline in the volume of fresh food shipped from the highlands to Port Moresby. The most common foods that are moved from the highlands to Port Moresby and other lowland centres are sweetpotato and potato. Others include cabbage, carrots and onions. In January and February 2020, prior to the COVID-19 lockdown, about 1,200 t was being shipped each week. This declined steeply in March. By April and May, the volume was down to 120–150 t per week (Table 6.9).

Table 6.9 Shipments of fresh food from Lae to Port Moresby (January–May 2020)

| Month | Volume shipped (t/week) |

|---|

| January | 1,220 |

| February | 1,208 |

| March | 406 |

| April | 120 |

| May | 150 |

Source: Fresh Produce Development Company, Goroka

Betel nut ban

A ban was placed on the transport and sale of betel nut during the state of emergency and lockdown. Betel nut is the most commonly consumed stimulant (psychoactive) substance in PNG. Its sale, transport and marketing is a major part of the rural and informal economy. Hundreds of thousands of rural and urban people earn cash income from this trade (Sharp 2016). The palm grows in the lowlands and up to 1,100 m altitude, but not in the densely populated highlands (agroecological zones 7, 8 and 9, Table 6.2) (Bourke 2010:488). The large market in the highlands and all urban centres involves many actors in complex value chains.

The ban on transport and sale of betel nut resulted in a large reduction in its availability and an increase in the price. Lowland betel nut was both scare and particularly expensive in the highlands. The ban reduced the income of many producers, intermediate traders and retailers of betel nut, as well as loss of enjoyment for the many consumers. In Jiwaka Province, some people climbed the mountains above the Wahgi Valley to collect self-sown highland betel nut (Areca macrocalyx), known as kavivi in Tok Pisin, and sold it as a betel nut substitute.

Impacts on women, particularly market sellers

Most market vendors are women (and girls), and many lost much or all of their income from growing and selling food and other items in markets. This income loss has a knock-on effect for family welfare, including the ability to pay children’s school fees, purchase foods with a higher content of protein, oil and fat than garden food, and buy phone credit. This is reflected in many of the women’s case study stories from Jiwaka and elsewhere.

Many vendors were forced to sell their produce at newly established markets (for example, outside Lae and Goroka), sometimes in unsanitary conditions besides drains. Women reported that curfews meant that it took much longer to sell their produce (for example, in Goroka, four days compared to two days before the curfew to sell 60 kg of sweetpotato tubers) (FAO 2020b).

Some intermediate traders went to a lot of effort and expense to purchase produce, avoid the police roadblocks and sell their produce in other smaller and informal markets. Drivers of public motor vehicles also risked arrest and fines to deliver food to urban markets in some locations.

In some locations, buyers from the towns went to the newly established markets outside the town boundary (for example, Goroka). In other places, urban people drove to police roadblocks in order to purchase fresh food from nearby vendors (for example, in Simbu province where the two fresh food markets in Kundiawa were closed).

There were people who benefited from market closures and lockdowns by charging higher prices when there were far fewer fresh food sellers (for example, near Buka township). Similarly, fresh food purchased in rural locations was sometimes sold at a high price in urban areas by those with travel passes, vehicle access and adequate resources.

The case study stories highlight the increased risk of gender-based domestic violence, decreased mobility, reduced access to police and the justice system, and an increased burden of care for family members locked down at home.

Purchasing, processing and selling agricultural commodities

This section outlines the impacts of the lockdown and decline in economic activity with respect to purchasing, processing and selling agricultural commodities that are exported or sold in distant markets in PNG. Impacts were uneven between commodities, between locations and over time. The greatest impact was on those selling fresh food and betel nut (as described earlier), with a significant impact on those selling vanilla and rubber (minor cash crops). People selling fish, chickens and meat suffered from loss of income during the state of emergency, but it is not possible to determine how great this was. Processors and exporters of Arabica coffee report that the volume being offered for sale is down in 2020, but this is not related to the COVID-19 crisis. Impacts on cocoa, copra and palm oil production and sales were both limited and short-lived.

The following short summary is organised by the economic value to rural people, as distinct from the value to the national economy (Bourke & Harwood 2009:Table 5.1.1).

Fresh food

Sale of fresh food, including root crops, banana and vegetables, is now the most important source of cash income, at least by total value. There are very many households engaged with selling fresh food, and income per person is generally less than for some of the export crops, betel nut and some animal products. Closure of fresh food markets in most urban centres had a huge impact on the income of many vendors, most of whom are female (Tables 6.7 and 6.8). This impacted on sales made close to the producing location, as well as the long-distance movement of fresh food from the highlands to Port Moresby (Table 6.9). Most of the larger intermediate traders contacted said that they continued to purchase and sell large volumes of fresh food to catering groups at mining and petroleum extraction sites. One company, which buys fresh food from farmers in one province and sells to catering groups in mining camps, reported buying less as some mines were operating with reduced staff numbers. For a short period, some vegetable growers in the highlands could not obtain vegetable seed.

Arabica coffee

The main harvesting period for Arabica coffee in the highlands is May to August. Information from four coffee processors in the highlands indicated that production was lower than normal in mid-2020. They do not attribute this to the curfews or lockdowns in the highlands, as these occurred in April–May, prior to the main harvesting season. Three reasons are offered for the low production:

- The Internal Revenue Commission has not refunded the goods and services tax collected earlier by processors and buyers. As a result, many buyers do not have sufficient operating capital to purchase parchment coffee.

- The Coffee Industry Corporation has not paid the freight subsidy to transport coffee by road from more remote locations such as Okapa or Menyamya or by air from locations with only air access. (Villagers in most locations near the Highlands Highway now invest more effort in growing and selling fresh food than coffee, so much of the coffee now comes from locations that are further away from the highway).

- Third-level airlines were impacted by the lockdown in March–June 2020, so coffee was not transported as back-load from remote locations such as Karimui, Marawaka, Simberi and Kaintiba. As well, many small airstrips have closed due to inadequate maintenance in the past decade or more.

The impact on coffee sales and processing in the first half of 2020 from the lockdown and state of emergency has therefore been minor.

Cocoa

Cocoa sales were reportedly impacted by the state of emergency for only a limited time in Madang and Milne Bay provinces. Cocoa exporters in Kokopo and Bougainville reported little or no impact on exports. Some concern was expressed that shipping issues could cause delays in the export of cocoa due to reduced shipping. This would cause beans to be held in storage at wharfs, which would in turn lead to loss of storage at buying depots and result in cocoa accumulating in villagers, which may impact on cocoa quality. However, storage issues have not arisen to date.

Betel nut and betel pepper

The ban on sales of betel nut in most urban centres and travel restrictions had a significant impact on the sale of betel nut and hence on the income of growers, intermediate traders and those selling to the public (see above).

Copra

People could not sell copra during the state of emergency and lockdown on Karkar Island (Madang province) and from islands in Milne Bay Province. There were no reports of copra shipping problems arising elsewhere.

Palm oil

The state of emergency did not have a major direct impact on production or processing of palm oil. Some initial issues arose in getting ships to transport palm oil for export, but these were resolved.

Fish and other marine foods

The case study stories reported adverse impacts on the sale of fish from the Sepik River and the sea in Wewak, as was the case in Alotau for the sale of smoked fish. Sales were likely impacted in some other coastal towns, but no information was available at the time of this assessment.

Livestock

Farmers growing poultry, pigs and fish for sale could access the respective animal feed in a number of highland and lowland locations (FAO 2020c). In markets where sale of meat and live animals was banned, people were not able to sell live chickens. It is not known how many people were able to sell them in informal markets or through other means. It was reported, but not confirmed, that a major producer of processed chickens in Lae stopped buying birds from village producers in Morobe Province.

Tobacco

The ban on inter-province travel during the state of emergency means that tobacco sales from highland to lowland locations were disrupted. Tobacco is commonly grown in mountainous locations and carried to coastal towns for sale, for example, from inland New Britain, the mountains in Central Province and inland East Sepik Province (Bourke & Harwood 2009:Figure 5.17.4). The impact of the lockdown on sales of village tobacco in these diverse locations is unknown.

Rubber

Most smallholder rubber is produced and processed in Western Province, with a small amount at Cape Rodney in Central Province. In Western Province, rubber continued to be harvested during the state of emergency. However, the MV Kuku could not travel to Lake Murray and Balimo to purchase cup lump rubber from villagers and transport it to Kiunga for processing. North Fly Rubber was forced to sell eight containers of processed rubber at a low price so that there was storage space for the cup lump that was purchased when the state of emergency was lifted. Thus, the state of emergency had a significant impact on the cash income of rubber producers in Western Province.

Vanilla

Producers and traders in East Sepik and Sandaun (West Sepik) provinces who normally sell vanilla in Jayapura (West Papua) were unable to travel there, so their incomes were impacted. It was reported that vanilla could not be exported from Madang when the port was closed for a period in March–April 2020 and vanilla growers could not sell their produce at this time.

Honey

The main honey producing period is around November–December, so the state of emergency and related lockdown and border closures had a limited impact on sales, according to the largest buyer, New Guinea Fruit. Nevertheless, some suggested that less honey was sold in April, while others reported the sale of honey ‘by going around the lockdown restrictions’.

Other parts of the formal and informal economy

Beyond marketing fresh food and betel nut, there were impacts felt in other parts of the formal and informal economy. Interviewees and case study stories (for example, Lae, Bougainville, West New Britain) reported the loss of income by many who derived cash income in the informal sector and in casual wage employment. A high proportion of people living in or near towns derive income from reselling fresh food (which they purchase from growers), cigarettes, betel nut and manufactured goods purchased from larger Chinese-owned stores. Reports from many towns indicated that men and women who operate small stores and sell processed food lost much of their trade because of reduced activity in the local economy.

Many people who depend on wage employment in urban centres and some rural locations became unemployed due to the state of emergency, making their lives more precarious. This was particularly the case for those engaged in road, sea and air transport, hospitality (cafes, restaurants, hotels), accommodation and tourism. Many expatriates, including Australians, left PNG at the start of the COVID-19 state of emergency, resulting in the loss of income for businesses that cater for expatriates, particularly in Port Moresby.

There are no quantitative data on the number of people affected by loss of employment, but anecdotes received from many urban centres suggest large numbers. This created particular hardship for those without access to food gardens or other sources of cash income. As of late July 2020, indications are that many in this situation have not yet found wage employment again. This is supported by some of the case study stories.

The impact on those in urban and peri-urban settings who had lost their wage employment has not been documented. It is highly likely that their consumption of fresh foods decreased because of the increase in prices of fresh food, particularly in the cities of Port Moresby and Lae. This is likely to have resulted in a less nutritious diets with implications for their health.

Sales of other commodities were also impacted. The demand for sugar from Ramu Agri-Industries was reported to have decreased by 20–30% in April–May 2020 and demand increased somewhat after the lockdown ceased. There was a reduction in demand for sugar to manufacture ice cream as consumption dropped.

Larger companies which produced and sold processed or imported food, including rice, flour, baked products such as biscuits, noodles, canned soft drinks and tinned fish, were initially impacted by the closure of provincial borders in early April 2020. For a short period, they were unable to move produce from Lae and Madang into the highlands. However, they responded quickly to obtain travel permits for their trucks and these goods commenced to flow again. Villagers selling fresh food in urban areas were not in a position to do this, so the impact on them was much greater.

Despite concerns by many based in urban centres, there were no shortages of rice, which is the staple food of most people in Port Moresby and many other urban centres. Trukai Industries reported that they had more than adequate stocks of imported rice stocks in March–May 2020 and there were no supply issues beyond this period. The sale of rice by Trukai contracted by up to 15% in April, with a slight recovery up to mid-June. Since mid-June, sales have been 3–5% lower than normal. This is a useful index of overall economic activity for both rural and urban people. A large company that manufactures biscuits reported an initial boost of 20% in sales of biscuits in late March as many urban residents stocked up on provisions.

Those in well-paid employment in urban centres were not impacted as much as those in the informal sector or those who lost their jobs. This was reported from Port Moresby and some other urban centres.

The limited number of passengers who could enter PNG from Australia or Singapore had to stay in quarantine in hotels in Port Moresby for two weeks. This inhibited some foreign workers, including those from the Philippines, from leaving PNG to go home on leave. Postal services into and out of PNG were disrupted by the change to international air transport.

Transport availability and costs

Closure of provincial borders meant that many men and women could not travel to sell produce, purchase agricultural inputs and, importantly in some locations, access medical assistance.

There were restrictions on the number of passengers that public transport operators were allowed to carry, and many increased their fares for both short trips within urban centres and inter-town travel. Goro (2020) gave many examples of such increases, with some inter-town fares doubling and others trebling. A Lae resident reported:

Social distancing was enforced on PMVs [public motor vehicles] which were only allowed to fill them to half of their capacity. To compensate PMV owners, bus fares in Lae doubled and this was a directive from the Department of Transport. This had a major impact on people, especially those supporting school children and paying for their bus fares. There is now little to no enforcement of social distancing on PMVs but people are still paying double.

In Alotau it was reported that: ‘PMVs were forced to carry half as many passengers because of social distancing, but they could not increase their price. Many have stopped running’. In East New Britain, public motor vehicle fares increased during the state of emergency, for example, from K3 to K5 from Kokopo to Rabaul. As elsewhere, fares had not returned to normal by the end of June (FAO 2020c). The state of emergency and lockdown also impacted those travelling by sea in some locations. In Milne Bay, many dinghy operators had less business as fewer people were travelling between islands.

Loss of cargo capacity by air transport made it more difficult for farmers to transport fresh food from the highlands to Port Moresby (FAO 2020b). The cessation of air transport also impacted the supply of food to schools, with some children having to return to their villages (for example, boarders at Mougulu High School in the Strickland-Bosavi sub-region of Western Province).

6.4.4 Recovery and resilience

It is too early to assess how well people have recovered from the impact of the state of emergency and lockdown from late March to late June 2020. Given the impact on the PNG economy, it is likely that many people will take a long time to recover from these events, if at all. In an analysis of poverty and the pandemic in the Pacific, Hoy (2020) concluded that the number of people living in extreme poverty in PNG (as well as Timor-Leste, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu) may increase rapidly due to the economic impact of COVID-19. Prior to COVID-19, around a quarter of PNG’s population lived in extreme poverty (i.e. below A$1.90 a day) (Hoy 2020). The qualitative information recorded in this assessment is consistent with this conclusion.

The case study stories and interviewees indicate that most people anticipate relying mostly on their own networks for assistance and information. Many gave examples of how people in villages and urban and peri-urban centres responded to the lockdowns, including:

- setting up new roadside markets outside urban centres

- moving food, betel nut and other goods around (or through) roadblocks

- risking fines and confrontations with the police

- driving from towns to the new food markets or closer to where producers live.

A number of informants commented on the need to give greater support to production of vegetables and fruit in home gardens, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas. There has also been greater interest in raising chickens (FAO 2020c).

In some locations, authorities and non-government organisations devised innovative ways to help villagers sell their fresh produce under the state of emergency. In East New Britain, the Market Authority worked with local government authorities to designate locations where food could be sold close to where it was produced, and from where it could be transported to a central location. The Market Authority plans to introduce ‘bulk selling’ where fresh food is bought and then sold to others who operate from roadside markets (FAO 2020c).

In the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Bougainville Youth in Agriculture, an initiative of the non-government organisation eDidiman, used their own technology to help farmers sell their fresh food, particularly those in more remote areas. Purchasers were encouraged to send a thank you text directly to growers as a psychological boost in light of the potential for the state of emergency to amplify traumas associated with the region’s past conflict.