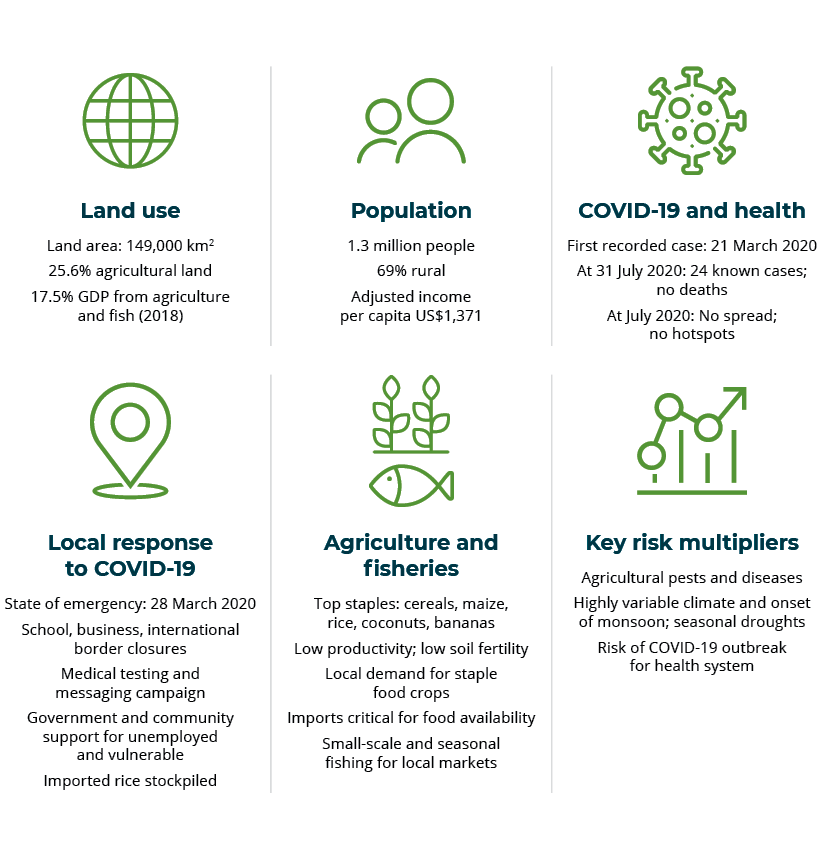

8.4.1 Snapshot of key findings

8.4.2 Exposure and vulnerabilities

A diverse and variable range of vulnerabilities has been exposed by the arrival of COVID-19 in Timor-Leste society, both directly in relation to potential health outcomes and indirectly across diverse sectors of the national economy. The degree and duration of these vulnerabilities will depend on multiple interconnected factors and will be shaped by any subsequent outbreak of COVID-19 infections and the extent to which the pandemic continues to disrupt the Timor-Leste economy.

Health vulnerabilities

One of the major challenges for government in post-Independence Timor-Leste has been the restoration and reinvigoration of a national health system to provide high-quality medical care to all citizens. Over the last decade, there have been significant advances in the development of a national distribution of health clinics and the provision of basic preventive health care, health messaging and improved training of health practitioners. This expansion has been supported by the growing services of Cuban-trained Timorese doctors (approximately 1,000 by 2017) and postgraduate medical training at the national university, the University of Timor Lorosa’e (Asante et al. 2014). Infant and child mortality rates in Timor-Leste have both declined by about one-third since 2009–10 (Kelly et al. 2019). The most notable trend is malaria incidence, which fell from 32 per 1,000 individuals to virtually zero over the past five years, leaving the country poised for malaria elimination (Kelly et al. 2019:11).

Despite these advances, the provision of accessible and reliable medical services, and health information3, including sexual and reproductive health services, remains patchy and thinly distributed across the country. Diagnostic and specialist medical equipment and services in regional hospitals are basic and limited. Although health care is nominally freely available, there are a range of costs and cultural barriers that limit access for the poor (Price et al. 2016). In a country still grappling with the legacy of a generation of military occupation, there are very limited mental health services and trained practitioners. Most people in rural areas source healing services via a range of local traditional remedies and divinatory procedures.

Timor-Leste has managed to successfully avoid the first wave of COVID-19 infections, but it remains highly vulnerable to subsequent outbreaks and poorly equipped to handle any major increase in demand for intensive care nursing. According to the Global Health Observatory, there were just 59 hospital beds per 10,000 people across Timor-Leste (Chen 2020).

Food and material supply chains

One of the consequences of constrained in-country food production is that there is currently a reliance on significant imports of staple food supplies, especially Vietnamese rice (100,000 t per annum), that are cheaper than locally grown product and account for around 60% of consumption (Young 2013). Since 2007, there has been a growing reliance on imported frozen chicken meat and eggs, especially from Brazil (16,561 t of frozen chicken meat and 3,850 t of chicken eggs, worth $US12 million in 2018), as well as flour, sugar, palm oil and seafood from Indonesia (ADB 2019). These imports have in many cases constrained the emergence of local import substitution businesses in direct food production and processing (Rola-Rubzen et al. 2011).

The absence of any real manufacturing base in Timor-Leste means that there is an extensive list of imported products and commodities (US$470 million in 2018), including palm oil, tobacco, vehicles, cement and building materials, that provide important contributions to the national economy. The only significant commodity export of any scale, apart from oil and petroleum, is Timorese Arabica coffee, which is produced by cooperative-based smallholders and generated US$20 million in 2018.

High dependence on the sovereign wealth Petroleum Fund

Timor-Leste remains one of the three most oil-dependent countries in the world. Oil and gas revenues account for 70% of gross domestic product and almost 90% of total government revenue between 2010 and 2015 (IFAD 2017). This has been a great bounty and source of financial security for the newly independent nation. However, the impact of this heavy reliance on the Petroleum Fund has created conditions for the debilitating and now-familiar distorting impacts of the resource curse (Bovensiepen 2018, Scheiner 2019). The nation remains highly dependent on the Petroleum Fund to support development programming and effective governance across the nation. The Petroleum Fund contributes a major share of annual state budgets—83% in 2017 (Scheiner 2019:93)—and is projected to continue at levels beyond the sustainable drawdown rate. The recent volatility in global markets saw the Petroleum Fund lose US$1.8 billion (10%) in value due to financial market shocks (Lusa 2020). Massive infrastructure investments by government have been criticised in the absence of persuasive analyses of the anticipated benefits (Bovensiepen 2018, Scheiner 2019). Without any new prospects for oil extraction from reserves (such as the Greater Sunrise Field in the Timor Sea), the need to diversify revenue sources away from fossil fuels is increasingly pressing (Neves 2018).

Women and gender vulnerabilities

Rural women in Timor-Leste experience low incomes and have major responsibilities for domestic work, carting water and firewood, caring for children and the sick, as well as contributing to farming, trading and purchasing in markets and the raising of livestock. Women typically have lower literacy rates (20%) than men (41%), and generate on average 15% less agricultural produce than their male farming counterparts (Gavalyugova et al. 2018). The COVID-19 restrictions and shortages have increased these livelihood pressures and affect women disproportionately (FAO 2020b).

The legacy of conflict and poverty across the country has, for some time, focused attention on the entrenched culture of domestic violence in Timor-Leste. A demographic and health survey (2009–2010) found that 36% of married women had experienced physical, sexual or emotional violence by a husband or partner, and just 24% of women reported the assaults. Women most often sought help from their own family (82%). Only 4% sought help from the police (JSP 2013:3, Gerry & Sjölin 2018). Women risk being rejected by their families and social networks if they involve the justice system.

Given the entrenched nature of domestic violence, the economic impact of COVID-19 is likely to exacerbate existing pressures on households and perpetuate violence in the household4. The European Union and the United Nations Resident Coordinator have dedicated US$1 million from the flagship Spotlight Initiative to address the increased risks of violence against women and girls in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (UNFPA Timor-Leste 2020).

Vulnerabilities in agriculture

Seasonal crop production

Across Timor-Leste, a majority of households (more than 200,000) practice forms of seasonal rainfed agriculture focused on the cultivation of maize and beans, as well as a range of secondary food crops including cassava, sweetpotato, pumpkin, squash and diverse tubers (da Costa et a.l 2013). On the southern littoral, an extended wet season permits a second cropping season. Most of the harvested food is used for home consumption or local market sales.

Men and women actively pursue farming with the understanding that harvest success is dependent on highly variable monsoon weather conditions and a range of unpredictable environmental factors, including droughts, weeds, plant diseases and pests, high winds and floods, as well as post-harvest storage losses due to a combination of weevils, rats and spoilage (>30%) (da Costa et al. 2013). Crop losses are common and many families experience food insecurity, particularly when household stores are exhausted and the new harvest has not been secured. Timorese refer to this period (usually December–February) as the hungry season (tempu rai hamlaha). Households are forced to rely on foraged wild foods, go into debt or sell assets to cover shortages (da Costa et al. 2013, McWilliam et al. 2015, Erskine et al. 2020). According to one report, 62% of households experienced food shortages for more than one month (Provo et al. 2017, Gorton 2018).

Food insecurity is a common experience in the hinterlands and mountains of Timor-Leste, and it contributes to the regularly reported poor nutrition and high poverty rates. A recent WFP survey found that few households (15–37%) could afford nutritious diets (WFP 2019). At the same time, generations of farming practice and the challenges this involves, including the possibility of outright crop losses, means that rural Timorese farming communities are also highly resilient in relation to the conditions they face. Vulnerability and resilience are closely related and are familiar experiences across the rural hinterlands and mountains. Many families cope with food shortages and poor nutrition on a regular basis. In a continuing COVID-19 environment, these patterns of livelihood will persist in the absence of significant new investment in productive and climate-resilient agriculture.

Irrigated rice

Irrigated rice production has been cultivated in Timor-Leste for hundreds of years, but for most of that time on a very limited scale. It was only during the late Portuguese colonial period (1960s) that greater investment was directed to irrigation infrastructure, including opening up a number of new areas. These efforts were further developed and promoted during the period of Indonesian governance (1975–99), when massive investments in irrigation infrastructure and road transport transformed farming practices and greatly extended the popularity and cultural acceptance of rice as a high-status staple food. By 1996, for the first and only time, East Timor achieved rice self-sufficiency (Fox 2001). In 1997 rice production reached more than half the tonnage of maize (Pederson & Arneberg 1998:33). In a post-Independence and COVID-19 Timor-Leste, this level of production in rice has not been sustained. Rice production has been in a long-term decline, due to a number of inter-related factors, even though rice has become the preferred staple food.

The destruction that accompanied the withdrawal of the Indonesian armed forces and the pro-Jakarta militia included substantial elements of irrigation infrastructure. Designed irrigation capacity declined by nearly 50% to around 34,649 ha (FAO 2011). In the two decades since, the remaining irrigation infrastructure and the road networks that connected production areas to markets and urban centres have also deteriorated. It is only in recent years that major investment in road and irrigation infrastructure restoration has been initiated and funded through the Petroleum Fund.

The use of fertilisers and pesticides, subsidised during the Indonesian period, have decreased significantly due to a lack of supply and the absence of private-sector traders and investors in the sector. There has also been a growing resistance among smallholder farmers to perceived investment risks. Production yields of rice have also declined from an already low base (1.6–2 t/ha) and most production is consumed or sold locally.

Consistent with trends across South-East Asia, large numbers of young people are resisting a career in smallholder rice production in favour of further education and easier and potentially more rewarding livelihoods in the towns and cities, even as youth unemployment remains a pressing problem. The result is the emergence of an ageing rural labour force (average 41 years) and labour shortages in rural areas, along with comparatively high labour costs (US$5–6 per day) and reduced areas under production.

Since 2007, with the initiation of drawdown from the Petroleum Fund, growing amounts of cheap milled rice from Vietnam are now imported and sold widely in local markets across Timor-Leste (Young 2013). The impact of importing 66% of national rice consumption demand has undermined any realistic attraction among smallholder farmers to increase rice production. When farmers cannot compete on price, there is little incentive to produce more. Young (2013) argues that the scale of imports suggest that estimates of local rice production are greatly inflated.

In the face of these multiple and systemic constraints against increased local irrigated rice production, the optimistic goal for Timor-Leste of ‘self-sufficiency in rice production by 2020’ as articulated in the Timor-Leste Strategic Development Plan 2011–2030 (Sustainable Development Goals 1 and 2) has failed and is unlikely to be achieved in the life of the planning document. A national agricultural census is currently being completed and is due for release during 2020. Hopefully, this will provide a more accurate assessment of local rice production and institutional support frameworks.

8.4.3 Impacts of COVID-19

Health

As of mid-July 2020, the direct impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been minimal, with no reported cases for many weeks. This good fortune for Timor-Leste has allowed authorities to strengthen their medical protocols and facilities in readiness for any future outbreaks. However, the risk of outbreaks of COVID-19 remains high, due to the lightly patrolled land border with Indonesia and the need to maintain imports and trade arrangements. In the absence of a vaccine and effective treatments, the need to open up the economy and increase social engagement will increase the risk of a subsequent wave of infections, which could have devastating impacts and quickly overwhelm the hospital system. Despite significant investment over the last decade, the national health system has very limited diagnostic and medical expertise available. At this stage, the major impacts of COVID-19 are indirect and economic.

Informal sector employment

The declaration of a state of emergency in Timor-Leste on 28 March 2020 set in train a coordinated lockdown of international and internal borders and the general closure of schools and most businesses, which led to extensive job losses in the informal sector. This had immediate impacts across the country. The informal sector provides around 60% of employment opportunities across Timor-Leste and employs up to 250,000 people. This category of work includes seasonal agriculture and a wide range of low wage, often intermittent, remunerative employment for people including farm labourers, shop assistants, security workers, market traders, taxi and bus drivers, domestic workers and hospitality staff.

The closure of businesses, across both formal and informal sectors, along with the return of many urban residents to their home villages has had a significant impact on women’s incomes and purchasing power, as well as increased workloads for women who take the primary responsibility for raising children and managing domestic arrangements including raising animals. Some 66% of employed women are self-employed farmers.

Tourism services, which are a growing non-oil sector of the economy, have also been severely hit by border closures and the departure of many expatriates. Given the high dependency ratio in Timor-Leste (71.2% in 2019, with many people relying on fewer providers), the effect on household incomes and consumption has been rapid. Reports indicate that people who lost their employment in the city have returned to their villages of origin, where living costs are lower and support from family members is available (Barnes et al. 2020a).

The loss of household incomes as a result of the emergency shutdown was a major shock and prompted the government to introduce temporary financial payments for over 300,000 households, amounting to US$100 per month for three months. These measures highlight the widespread impact of income loss, the absence of household savings and the subsequent rapid emergence of food shortages.

Food supply chains

As noted above, Timor-Leste is highly dependent on a diverse range of food supply imports. Apart from some initial concerns about securing additional shipments of rice for stockpiling, these matters have been resolved and the major food importers (Kmanek, Centro and Miemart) have been able to ensure continuity of supplies (MDF 2020). Some disruptions and delays have been caused by the closure of the land border with Indonesia. Timor-Leste custom operations have been operating for just two hours a week to process cross-border commodity flows, with predictable delays. At the start of June, 40 trucks belonging to 17 Indonesian logistics companies were waiting to bring five tonnes of food items into the country (MDF 2020). Local food supply chains, particularly horticulture and fruit supplies, have been disrupted to varying degrees due to delayed agri-inputs and transport disruption. However, over recent months, food supplies and price inflation of food and domestic retail items have remained relatively stable (WFP Timor-Leste 2020).

COVID-19 has reduced the demand for a number of export crops, such as coffee, copra, konjac and candlenut. Coffee is grown by up to 38% of farmers and disruptions to markets have direct and deleterious impacts on farmer household incomes. It is reported that the trading cooperatives, Café Brisa Serena and Alter Trade Timor have had export orders cancelled. It remains unclear if Indonesian traders who normally visit Timor to purchase coffee will visit in 2020, as a result of travel restrictions and a weakened Indonesian rupiah (MDF 2020).

Smallholder agriculture/horticulture

In the 2019–2020 cropping season, delays in the onset of rains and reports of below average harvests have been reported in regions of the island (for example, Baucau, Atauro, Oecussi). These reduced returns, which may have been affected by fall armyworm, have caused shortages and income deficits in a number of areas. However, the arrival of the COVID-19 emergency came at a time when most households had begun harvesting their main seasonal food gardens. This provided an opportunity to store grain and other secondary crops and generate income from crop sales to regional markets.

In the medium term, the scenario is more uncertain, not simply because of variable monsoon weather, but also because of the prospect of shortages of seed and agricultural inputs to support cropping and farm production. Timor-Leste is highly dependent on a range of vital agri-inputs, including seeds (especially for horticulture), day-old chicks, animal feeds, pesticides, herbicides, tools and equipment (MDF 2020), most of which come across the land border from Indonesian Timor. According to recent reports, a number of local suppliers have exhausted their existing stock or are unable to source new supplies. On the border, three logistics companies have had nine tonnes of agri-inputs held up by customs for two months (MDF 2020). These shortages will have direct impacts on the incomes of vegetable growers and market gardeners, as seed prices increase, or shortages continue. For example, among the few local broiler chicken producers, Vecom and Hanai Malu have already had to stop production because they are unable to source day-old chicks from Indonesia (MDF 2020).

Animal husbandry

As noted above, the COVID-19 pandemic was preceded by African swine fever, a highly infectious and lethal disease that was detected in Timor-Leste on 9 September 2019 and confirmed by the government on 27 September 2019. Over a number of weeks, a total of 100 outbreaks on smallholder pig farms were recorded in Dili. The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries formed a taskforce to put control measures in place and implemented ban on the movement of pig and pork products between districts.

Despite these early measures, African swine fever spread rapidly across the country. Outbreaks have been reported in the districts of Baucau, Covalima, Ermera, Lautem, Liquiça, Bobonaro, Manatutu, Manufahi and Viqueque. By early 2020, African swine fever had caused the deaths of up to 50,000 pigs (12.5% of total) (T. Barnes, pers comm, 2020). Some areas are reported to have lost most of their animals, which is a major disaster for many poor rural households. Recent attempts to update the impact of African swine fever in Timor-Leste suggest that outbreaks continue despite biosecurity containment and greater public awareness. Based on regional reports (MAF staff, pers comm, 2020), there appear to be greater losses in the central and western areas of the country than the eastern sector. This suggests that the ban on pig transport may be slowing the spread of the virus, with the COVID-19 emergency restrictions reinforcing those separations.

International labour migration

The growing expansion of formal and informal temporary international labour migration out of Timor-Leste was immediately and significantly disrupted by the declaration of a state of emergency, the closure of borders and quarantine restrictions. Formal migration programs are managed by the Timor-Leste Government through bilateral agreements with Australia (Seasonal Workers Program) and South Korea (Employment Permit System). There is an expanding demand for participation in these programs, which offer a number of pathways to higher incomes, savings programs and voluntary remittances to supplement source household incomes in Timor-Leste. Timor-Leste now has access to the Australian Pacific Labour Scheme for ‘semi-skilled’ workers, offering a longer time frame and wider work opportunities (Rose 2019).

Informal labour migration among young Timorese travelling on Portuguese passports to work in the United Kingdom in a range of low-skilled shift and factory jobs has also been popular since 2010 (McWilliam 2020). High rates of remittances to home households has been a prominent feature of this trend, which has provided significant direct benefits to participating families. Curtain (2018) has highlighted the growing contribution of remittances as a non-oil export industry. In 2017, this amounted to US$40 million, with around 65% sourced from the United Kingdom (Scheiner 2019).

The impact of COVID-19 travel disruptions and varying degrees of lockdown in different countries has had varying negative impacts on the migrant labour migration. In the United Kingdom, most hospitality workers lost work when restaurants, cafes and other businesses shut down, but other sectors were only lightly affected (for example, supermarket and food packaging businesses). In Australia, seasonal workers from Timor-Leste have continued to work and receive remuneration, and remittance flows via Western Union transfers have not been affected.

The main COVID-19-related disruption is to potential labour migrants who have not been able to travel to their planned destinations. With little or no alternative employment in Timor-Leste, certainly not with comparable wage levels, there is a growing backlog of frustrated applicants for overseas labour migration work, particularly young people.

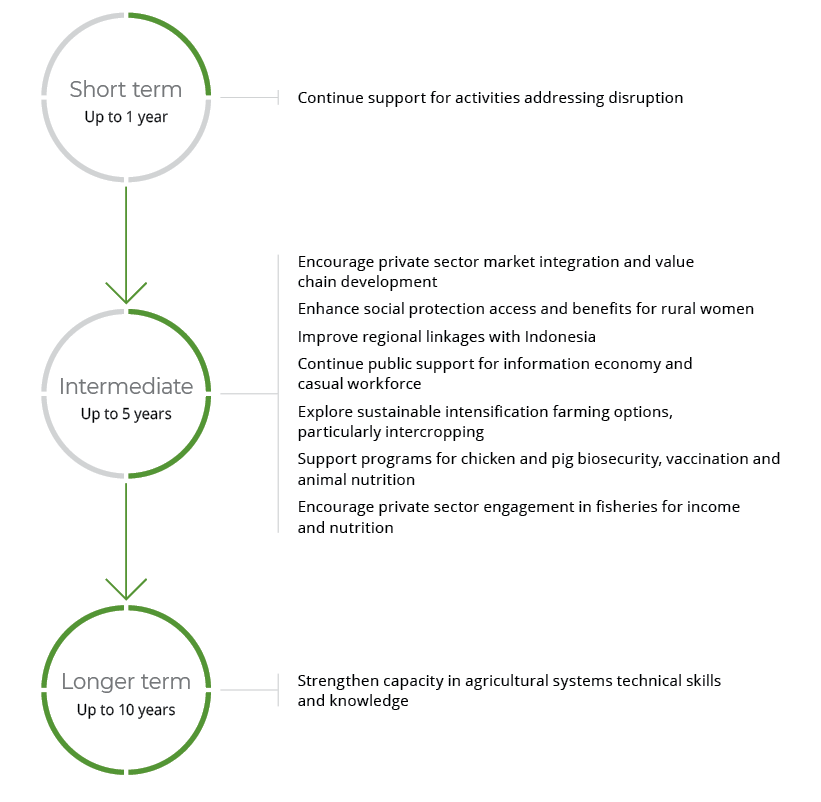

8.4.4 Recovery and resilience

As of late July 2020, with no records of new COVID-19 infections for two months, the economy of Timor-Leste has been gradually opening up. Dili is reported to be busy and operating close to normal, but with social distancing measures (distancia fisika) in place. It is anticipated that, for the continuing period of extended emergency, the only restrictions will be the closure of the international border for travel with Indonesia and restrictions and conditions on entry to Timor-Leste by expatriates (two weeks quarantine) and foreigners (excluded, with some exceptions). Trade and import–export arrangements will remain open but will be prone to disruptions and stoppages in supply chains.

As Timor-Leste adjusts to the COVID-19 conditions and prospects for a period of continuing uncertainty, it is appropriate to consider the prospects for economic recovery and the renewed enthusiasm for continuing the nation-building process that Timor-Leste has been engaged in since Independence in 2002. This section highlights a range of key areas that will provide sources of recovery and resilience.

The Petroleum Fund as a safety net

During the recovery phase in a continuing COVID-19-constrained environment, Timor-Leste remains heavily reliant on the Petroleum Fund for recurrent spending in the foreseeable future. There is a growing urgency to generate additional oil and gas revenues from new developments (not a short-term prospect) or hasten towards non-oil sources of revenue and income. Both prospects face significant challenges and the looming crisis may force a reappraisal of current investment priorities.

At the same time, with the success of the recent nationwide cash transfer measures for 318,000 households in response to COVID-19, continued use of the multibillion-dollar Petroleum Fund to support vulnerable households directly for longer periods may be both necessary, popular and politically persuasive. On 24 June 2020, the parliament approved a second extraordinary transfer of US$287 million from the Petroleum Fund to strengthen state accounts and the COVID-19 fund to ensure normal administration prior to the approval of the 2020 State General Budget (Tatoli 24 June 2020).

Informal sector employment

It is likely that much of the informal sector will begin to recover with the lifting of the state of emergency and the resumption of economic activity. These activities include market trading and transportation services, regional agriculture and fishing activity, market gardens, cleaning and security services, shopkeepers, hairdressers and building activities. As long as Timor-Leste continues to be free of any renewed surge in COVID-19 cases, many aspects of the precarious informal sector will gradually return to 2019 levels of activity. This will have significant flow-on benefits to the many households that depend on these forms of income. One with significant potential to provide enhanced household incomes and improve local food supplies is small-scale horticulture, particularly higher-value seasonal vegetable production (Rola-Rubzen et al. 2011).

Other employment sectors are likely to remain subdued or inactive, with increased risk of extended hardships for business operators, especially tourism-focused businesses (for example, homestays, tours, dive tourism, vehicle rental, restaurants and affiliated enterprises). In these circumstances, there will be a need for further government budgetary support in the light of continuing high unemployment. The continuing disruption to women’s incomes will also have proportionate impacts on many rural and urban households.

Off-farm income

Another common feature of rural household livelihood practices is the general need to secure off-farm incomes during the dry season or after the main food harvest. Farmer households tend to be opportunistic in these practices, focusing on activities and prospective local resources that provide quick cash returns. Men and women are active in these seasonal activities, which include bamboo, palm thatch and firewood sales to passing traffic, selling construction timber and other building materials, handmade textiles, sea salt, wild honey, fish products, horticulture and the production of vegetables for urban markets, as well as small-scale trading, off-farm labouring on roads or construction crews, and the production of fermented and distilled palm liquor (tua sabu), which is widely consumed and used in local rituals. These diverse off-farm supplementary activities are likely to pick up again as transport links and market activity resume. A minimum level of cash is required to purchase domestic essentials and groceries, including noodles, cooking oil, salt and imported rice, which has become a favoured food.

Animal husbandry

The majority of rural households and many urban families integrate animal husbandry into their smallholder livelihood activities. The 2015 census found that almost all households (97%) own livestock, 96% raise pigs and 79% raise local chickens, for the most part on a free-roaming scavenging approach to animal husbandry. Cattle and buffalo ownership among households is lower (23%), which is a reflection of their higher unit cost, but they remain an important component of agricultural livelihoods in Timor-Leste.

Pigs and African swine fever

Historically, pigs are the second most numerous livestock species raised in Timor-Leste (87.2% of households) with a total pig population of 419,169 (Direcção Nacional de Estatística 2018). Pigs are important in traditional ceremonies and represent the greatest contributor to monetary income from livestock. The most common pig-raising system is a free-roaming scavenger system, but some pigs are raised in semi-confined or confined systems with supplementary feeding, often by women and girls. Availability of feed is a key constraint, especially in the dry season, and is the principal reason that pigs are allowed to roam freely in villages and scavenge for food.

The emergence of African swine fever in 2019 added another major risk to smallholder pig rearing. Over time, as the threat of African swine fever in Timor-Leste moves from an epidemic to an endemic situation, there is a need for more widespread and reinforced public education on how to reduce the risk of disease to enable communities to raise pigs safely (Barnes et al. 2020b). It should be noted that Timor-Leste already hosts classic swine fever, for which a vaccine is available but rarely delivered. There is no vaccine for African swine fever to date. The difficulty here is that the added costs to establish household-based biosecure rearing practices for their animals (pens, fencing, disinfectants, feed and clean water) may be prohibitive, with no indication of support from the government extension services.

Pigs are highly regarded by Timorese households. They are a store of wealth and they play a vital role in familial exchange practices (Umane-fetosawa) and expectations that inform social relations in Timor-Leste communities. While this varies around the country, all life-cycle transitions (births, marriages, deaths, end of mourning, new house commemorations, and so on) engage a network of agnatic and affinally5related households, whose connections and contributions are acknowledged with reciprocated gifts. Pigs, cattle and buffaloes play an important ceremonial role in these ritual settings, both as gifts to be exchanged and as contributions to commensal feasting. In addition, although the majority of Timor-Leste citizens are Catholic, ancestral religion remains an important focus for many communities. Sacrificial veneration of ancestors and the use of divination requires the sacrifice of piglets and chickens both as offerings and as the basis of shared meals. As a result of these factors, the dramatic loss of pigs to a new and lethal virus is not only a financial shock to households but has broader impacts on nutrition and the consumption of meat protein (Wong et al. 2020).

Poultry

Chickens are a ubiquitous feature of village and urban life in Timor-Leste. Small numbers are raised by the great majority of households for egg production and are used as a source of cash income or for ritual purposes. Chickens are raised mainly by women (Wong et al. 2020) on a free-roaming scavenging basis (except for fighting roosters used in cockfighting).

Chickens are also the most commonly eaten meat in Timor-Leste (GDS 2011), but stock losses are high due to predation in young birds from cats and snakes. Knowledge of improved husbandry practices is poor and extension services are weak (TOMAK 2020). The main disease problem affecting flocks is Newcastle disease, which can kill large numbers quickly if there is an outbreak. It is also common practice to consume sick or dead birds, which can have deleterious human health impacts (Wong 2018). There remains a risk of highly pathogenic Asian influenza entering Timor-Leste via the porous land border with Indonesia. Fighting cockerels are said to be much cheaper in West Timor and are easy to transport (The New Humanitarian 2008).

There is a vaccine for Newcastle disease, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries has an established program in the districts to provide vaccination services on a periodic basis. Lack of effective control of outbreaks is in part due to capacity constraints for Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries veterinary technicians in terms of meeting demand. The logistics of rural vaccination services also preclude effective coverage, as continuing regular outbreaks of Newcastle disease indicate (MAF staff, pers comm, 2020)6. In one ACIAR study, flock-level Newcastle disease sero-prevalence was observed (at least one bird tested had antibodies against Newcastle disease virus) and a total of 35.3% of flocks had a minimum of one bird being Newcastle disease sero-positive at least once over the study period (Serrão et al. 2012). Sero-prevalence usually provides an underestimate of Newcastle disease, as birds infected with velogenic strains generally die (R. Alders, pers comm, 2020).

There is a strong demand for both eggs and poultry meat in Timor-Leste, particularly in urban areas and Dili. For the most part, however, these products are supplied by imports rather than local chicken and egg production facilities. They come mostly from Brazil (16,561 t of chicken meat and 3,850 t of chicken eggs, worth US$12 million in 2018). According to Scheiner (2019:101), about 40% of the goods imported for consumption could be produced in Timor-Leste if agriculture, food processing and small manufacturing were improved. However, there are limited commercial poultry breeding and production facilities operating in Timor-Leste, even though the opportunity to improve local supply is significant. Limited private-sector interest and investment is another constraining feature for commercial chicken meat and egg supply, which will struggle to compete on price with imported products. There is significant opportunity and economic benefits to be gained from cost-effective private-sector investment in local poultry production.

Cattle and buffalo management

Like pigs, cattle (Bos javanicus) and buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) in Timor-Leste are prestige animals, acquired and lightly managed by households for participation in the complex exchange relationships of Timorese extended family life. They are also viewed as a store of wealth to be sold for cultural exchange purposes, or to fund household expenses. Communities across Timor-Leste have been building up their herds of (Bali) cattle and water buffalo, which were largely destroyed or disbursed in the destructive withdrawal of the Indonesian occupying armed forces in 1999.

Across Timor-Leste today, more than 150,000 cattle, 100,000 buffalo and 200,000 small ruminants (goats and sheep) graze some 200,000 ha of public lands, most of which is poorly managed open commons (Fordyce 2017). Grazing land is generally highly degraded with dense, woody and unmanaged herbaceous weed infestations (for example, Lantana camara, Mimosa diplotricha and Chromolaena odorata) with very low annual pasture production. The absence of improved pastures, overgrazing and seasonal droughts means that much of the stock is very underweight and significant stock losses occur due to lack of water and feed. Diseases such as brucellosis are endemic and, while not fatal to cattle, cause high rates of calf mortality. These persistent challenges are compounded by the limited availability of veterinary services—Fordyce (2017) reports just 15 qualified vets in the country—and a reliance on a small suite of remedies (antibiotics, antiparasitics and vitamins) to treat animals usually undertaken periodically by district-based veterinary technicians (MAF staff, pers comm, 2020).

There is growing demand for beef in urban areas but marketing, butchering and processing of beef products remains rudimentary. Reports of significant unrecorded sales of cattle into Indonesia markets across the West Timor land border (estimated at 5,000 per annum) due to more favourable pricing may affect the stability of beef supply in Timor-Leste markets (ACIAR project leader, pers comm, 2020). During the COVID-19, period, however, this trade has reportedly been disrupted.

Fisheries

Timor-Leste has a coastline of around 735 km and 72,000 km2 of Exclusive Economic Zone waters with rich marine resources and the potential to develop offshore fisheries, especially in the Timor Sea off the southern coast. Coastal and near-shore waters support modest numbers of artisanal and seasonal fishing activity—FAO (2019) estimate 20,000 fishers—with low-technology dugout canoes and motorised outrigger boats. Sales of fresh and dried fish are localised, with limited and fragmented distribution into hinterland markets and towns by motorbike. Average fish consumption in Timor-Leste is 6.1 kg per capita per annum, substantially lower than the regional Asian average of 17 kg per capita per annum (AECOM 2018:3). However, there is significant variation, ranging from 17.6 kg per capita per annum on the coasts (more than meat) and just 4 kg per capita per annum in the hinterland and mountains. Coastal communities also gain additional year-round supplementary nutrition through regular reef gleaning at low tide (mainly by women and children). Most artisanal fishing around the coast uses relatively low-technology fishing methods (line, net, fish traps and cages) and fish marketing remains localised and poorly coordinated.

In the 2011 National Strategic Plan, it was noted that, compared to other agricultural sectors:

‘(F)isheries is already well regulated with a number of laws, decree laws and ministerial diplomas directly relevant to the sector. However, there is little enforcement and the sector operates much as it has done in the past.’ (RDTL 2011:131)

Over the last decade, Fisheries (within the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries) has trialled a number of initiatives and programs, but evidence of any sustained development is minimal. A revised policy approach has now been developed (López-Angarita et al. 2019).

The establishment of a sustainable commercial fishing industry accessing the deeper waters of the Timor Sea off the southern coast is a national government strategic priority. However, this objective has proved problematic for a range of reasons, with numerous setbacks in planning and licensing of operators. Limited patrol of the marine Exclusive Economic Zone has been a factor in the illegal operations by foreign vessels in these waters. Licensing external operators has also proved fraught, and a number of fishing operations have been shut down and fined. There have been no licensed fishing operations operating in the Timor Sea since 2017 and a fish processing and canning factory developed in the eastern Lautem district in 2017 was abandoned upon completion.

On land, a number of pilot-scale aquaculture projects have been developed in Timor-Leste over the years, focusing mainly on freshwater milkfish and tilapia species production. These attempts have had mixed success. A recent New Zealand evaluation report noted at the end of a five-year technical support program that ‘the business case for aquaculture, including hatcheries, has yet to be proven’ and that ‘five years is too short a time period to establish a well-managed and sustainable aquaculture sector when starting from such modest beginnings and in such a challenging environment’ (AECOM 2018:3).

World Vision is providing COVID-19 hygiene and social distancing training through the Australian Humanitarian Partnership Disaster READY program.

A 2010 law against domestic violence defined domestic violence as a public crime and included physical, psychological, sexual and economic violence as prohibited forms of violence. There have been increased prosecutions since then, but there remains much scope for improvement (Gerry & Sjölin 2018).

All Timor-Leste language communities form around membership to ancestral clans (origin houses) based on either patrifilial or matrifilial kinship connections (i.e tracing membership through fathers and grandfathers or mothers and grandmothers). All of these kin groups are exogamous, meaning that marriage partners are found outside one’s ‘house of origin’ and the relationship creates lifelong patterns of gift exchange and reciprocal obligations via these affinal (in-laws) alliances (McWilliam 2011).

A thermo-tolerant vaccine developed by ACIAR and delivered via eye drops three times a year by trained community vaccinators has proved effective on a trial basis but needs to be scaled up (ABC 2016). www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2016-04-21/village-chicken-project-delivering-food-security-for-east-timor/7341888