The ACIAR mandate to commission research to identify and find solutions to agricultural problems of developing countries made it inevitable that one of its most significant and enduring partners would be Australia’s national scientific research agency – the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). Since ACIAR was established, it has supported approximately 270 projects in which a CSIRO scientist was project leader, and countless more projects where CSIRO staff were members of the project team.

The collaborations and partnerships between ACIAR and CSIRO have led to innovations benefiting agriculture in partner countries and in Australia. These innovations have lifted crop and livestock productivity, increased the efficiency of inputs and resources, and reduced adverse impacts of agriculture on communities and the environment.

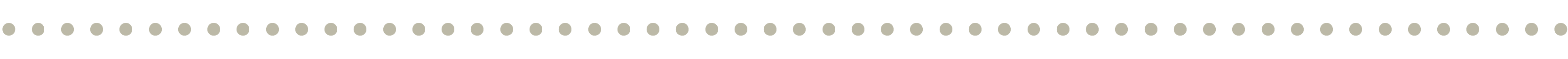

The crop modelling platform Agricultural Production Systems sIMulator (APSIM) is a classic example of innovation and ongoing impact arising from an ACIAR–CSIRO partnership. As an early career scientist with the CSIRO research team, Dr Brian Keating was posted to work on the project in 1985. The project was the first ACIAR-supported farming systems research in Africa in the 1980s and early 1990s (and the largest ACIAR project at the time) between partners CSIRO and the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute, under the title ‘The improvement of dryland agriculture in the African semi-arid tropics’. The aim of the project was to find effective management responses and affordable technological innovations to solve some of the problems of dryland farming in the semi-arid tropics.

‘The whole farm “systems” approach of the project was ambitious, and researchers had to develop new analytical technology to identify pathways to sustainably intensify maize/bean/livestock farming systems in semi-arid landscapes. A sister project was undertaken in Katherine, in Australia’s Northern Territory, and this saw Dr Peter Carberry start his long and successful career in CSIRO,’ said Dr Keating.

Informed by this research, CSIRO partnered with the crop and soil modelling work of the State of Queensland, and with training opportunities through the University of Queensland, in a joint venture.

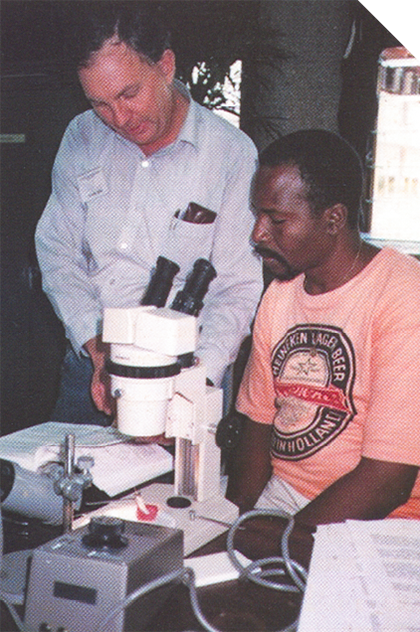

The resulting technology was APSIM, a software program to interpret and integrate data about landscapes, soils, climates, germplasm and farming practices. The program can run (model) simulations, based on the data, and in effect enable virtual experiments on ways to improve farming systems. APSIM meant research could truly address climate variability and risk in ways that otherwise require decades of experimentation. APSIM’s applications have extended from agronomic research to include on-farm decision support, the design of breeding programs, greenhouse gas mitigation and climate change adaptation research, and more recently continental-scale yield forecasting and analytics.

Not only was the approach itself groundbreaking at the time, but APSIM remains in use by agricultural scientists all over the world. The original design continues to be refined and developed with other partners to broaden its applications and develop the now internationally recognised and leading platform for scientists to model a diverse range of crop, animal, soil, climate and management options.

‘The farm systems model became a means to these ends rather than an end in itself, and the approaches and tools that the ACIAR projects of the 1980s and 1990s developed continue to deliver value in diverse partnerships around the world to the present day.

‘The impacts of the research program over the next 40 years went well beyond the APSIM model itself, to include a transformation in the way agronomic research was conducted in Australia and abroad, with shifts towards greater on-farm and participative approaches, stronger integration of socioeconomic considerations and greater focus on climate variability and risk considerations in technology development and adoption.’

In addition to the lasting legacy of APSIM and the new approaches to agronomic research developed during his time on the project, Dr Keating also described great personal rewards from being involved in the ACIAR-supported program.

‘My time in Kenya with ACIAR was transformational. In terms of problem-solving, building confidence and sheer research opportunities, it shaped my career. It was enabling and uplifting. And best of all, because of the way ACIAR is set up to promote research in both the partner country and Australia, it did not require a choice between working internationally and remaining engaged with promoting Australian agriculture. Looking back now, I can see how this experience ended up shaping the evolution of CSIRO’s capabilities in farming systems research over the last 35 years.’

Dr Keating acknowledges Dr Jim Ryan, Dr Gabrielle Persley, Dr Denis Blight and Professor Jim McWilliam as the visionaries who, alongside Sir John Crawford, were most responsible for creating the ACIAR partnership model, which is built on strong relationships with Australian research institutions.

‘CSIRO was always a strong advocate for ACIAR given the common interest in projecting Australian science into the wider world. Drs Ted Henzell and Bob Clements were CSIRO leaders who laid an incredibly strong foundation for the ACIAR–CSIRO partnership in the 1980s and 1990s.

‘So strong are those bonds that CSIRO has remained engaged in agricultural research aid in Africa every year since 1984, and the APSIM team is today the strongest in the world at computational modelling of farm systems.’

ACIAR partnerships are also career-shaping experiences for the scientists involved. Dr Keating is now Adjunct Professor at the University of Queensland and Chair of the Advisory Board of the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation (QAAFI). Dr Keating built on his work in Africa, to become a pioneer of the application of simulation models in farming systems research in Africa and Australia. He continued working for CSIRO throughout his career, including senior roles of Chief of Sustainable Ecosystems (2004–2008), Director of the Sustainable Agriculture Flagship (2008–2013) and CSIRO Executive for Agriculture, Food and Health (2014–2015).