Newcastle disease is caused by a virus that is deadly for chickens and some other poultry. It spreads rapidly within and between flocks, and commonly sweeps through villages throughout Asia and Africa. The disease kills many of the scavenging chickens that are important to these communities. Village chickens are often the only source of protein and micronutrients for smallholder farmers and also provide vital income. Up until the 1980s, it was impossible to control Newcastle disease in village chickens because the available vaccines needed refrigeration.

In 1984, Professor Peter Spradbrow of the University of Queensland and Professor Latif Ibrahim (1938–2022) of the Universiti Pertanian Malaysia were funded by ACIAR to research a vaccine that could provide protection from Newcastle disease in village environments. They developed a heat-tolerant vaccine (HRV4) that could be coated onto chicken feed. The research first focused on the vaccine’s use in villages in Malaysia, and then extended to other countries in South-East Asia.

The HRV4 vaccine was commercialised by an Australian company, which was later taken over by an American firm. However, affordability of the vaccine and distribution problems limited the initial uptake of the technology in the target countries. Recognising these problems, Professor Spradbrow gained support from ACIAR to develop a new avirulent vaccine, known as I-2, in 1995. From this seed vaccine the heat-tolerant vaccine can be made locally at low cost and administered to chickens in drinking water or by eye drops. This project also developed training methods for people in partner countries to produce the I-2 vaccine from seed stocks supplied free from Australia. The technology and training were also extended to Vietnam and a number of countries in eastern, southern and western Africa.

Research and vaccine development to combat Newcastle disease in eastern and southern Africa was consolidated under new ACIAR-supported projects from 1995 to 2001. Led by the University of Queensland, the projects in Africa resulted in development of comprehensive vaccine production, distribution and administration systems for the I-2 vaccine.

The ACIAR-funded research was followed by a series of projects funded by the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) that continued the Newcastle disease control activities in Mozambique and expanded them into Ethiopia, Tanzania, Malawi and Zambia.

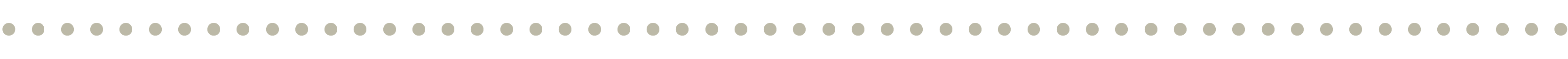

An impact assessment in 2013 concluded that total net benefits to the four African partner countries was estimated at around A$479 million, with A$80.6 million of those benefits attributed to ACIAR.

Dr Robyn Alders, now Honorary Professor at the Australian National University and a Senior Consulting Fellow with the Chatham House Global Health Programme, worked on the ACIAR-funded project in Mozambique. Dr Alders was involved in taking the thermotolerant vaccine from Asia and adapting its use for Africa. The project actively involved men and women chicken farmers, and a novel cost-recovery program involving community vaccinators for Newcastle disease was developed.

This made the vaccination program sustainable, without needing international resources. The cost-sharing model with village farmers has been adopted in many countries in Africa and Asia, including Timor-Leste, helping to increase biosecurity against poultry diseases in those regions as well.

In addition to economic and social benefits of the project in Africa and South-East Asia, the development of the new vaccine strengthened Australia’s management of poultry diseases.

‘In terms of clinical signs, you can’t tell the difference between virulent Newcastle disease and highly pathogenic avian influenza. This makes it difficult to rapidly identify outbreaks of avian influenza in regions where farmers are accustomed to seeing chickens die regularly from Newcastle disease,’ explained Dr Alders.

‘When farmers believe that the vaccine will prevent Newcastle disease, they are willing to pay a fair price for the vaccine and its administration by community vaccinators. Because of this investment, should vaccinated birds then die, those farmers are more likely to report that death. That then provides a more sensitive surveillance system for highly pathogenic avian influenza.’