Securing seed, skills and food for a nation

More than 65,000 families benefited from the Seeds of Life program, which ran in Timor-Leste from 2000 to 2016.

Seeds of Life started as a one-year project to improve food security by introducing higher-yielding crop varieties.

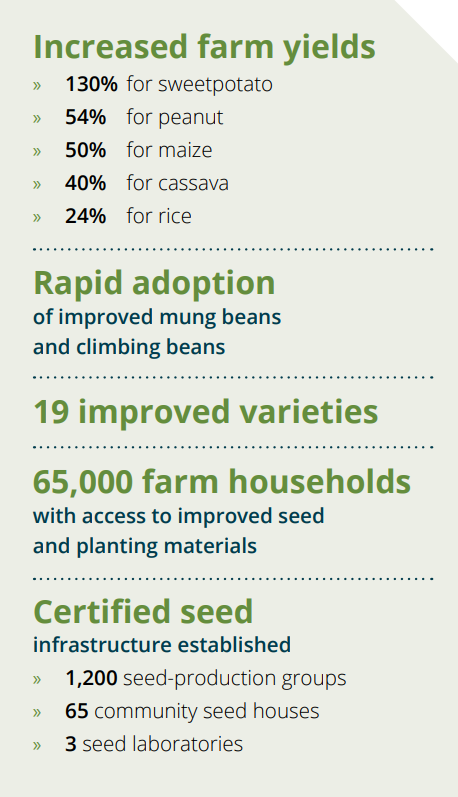

It finished as a suite of three projects that introduced 19 new varieties of major staple food crops and established a national seed system, so village farmers could maintain access to high-quality seed and continue to improve crop production beyond the life of the project.

In 2000, after many years of disruption to village life and farming during Timor-Leste’s journey to independence, an ACIAR-funded project reintroduced germplasm of staple food crops such as rice, maize, peanuts, sweetpotato and cassava.

The yields of the new varieties were promising and led to a second project to confirm the acceptability and benefits of the new or improved varieties in farmers’ fields. Several thousand farmers across the country participated in this work. AusAID (now incorporated into the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade [DFAT]) invested in this project, in partnership with ACIAR, to expand the activities of the previous project and develop processes to sustain its benefits.

The first two projects showed that the benefits of the new varieties in terms of increased production and increased food security were clear.

Over 16 years, the University of Western Australia led the project and worked in close partnership with the Timor-Leste Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Drawing on global resources

In the 1990s, a lack of good varieties of staple food crops was limiting crop production in Timor-Leste, to the extent that it was threatening national food security. The Seeds of Life program, overseen by ACIAR Research Program Manager Dr Colin Piggin, changed from a humanitarian operation to an agricultural extension program with the development of commercial crops as the ultimate goal.

Seeds of Life had its genesis in the aftermath of the violent reprisals after the population of Timor-Leste voted for independence in September 1999. Seed for the next harvest was either burned or stolen. ACIAR contacted the world’s five leading crop research centres for suitable supplies and by December 2000 the first test crops were being sown.

The program established trials of irrigated rice, maize, peanuts, sweetpotato, cassava, mung bean and climbing bean. The program also identified varieties that were more tolerant to prevailing insect pests and diseases, and able to withstand periodic drought and reduced soil fertility. The yields of introduced and adopted crop varieties were remarkably higher than yields of local varieties in all 13 of the nation’s districts where trials were established.

Many international agricultural research centres within CGIAR were key partners in the program, including the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) and the International Potato Center. The centres host gene banks for the staple food crops and provide material for breeding programs.

Dr Harry Nesbitt, Adjunct Professor at the University of Western Australia and Project Director for Seeds of Life, described the wide-ranging benefits of the project.

‘From an increase in human capacity to improved scientific infrastructure and increased agricultural production by farmers, the Seeds of Life legacy is everywhere. I’m happy to see how much Seeds of Life continues to help people.

‘Importantly, the agronomic research, seed multiplication and distribution system [that were developed are] sustainable, ensuring the legacy of the program lives on.’

ACIAR recognised the need to improve our staple crop production and designed a research program to help identify those crop varieties … One of the reasons for the widespread success of Seeds of Life is its commitment to educating our agricultural scientists so that we are not dependent on foreign expertise.

José Ramos-Horta

Timor-Leste President (2008–2012)

Partners in Research for Development

30th Anniversary edition 2012

Genuine collaboration with farmers

Through thousands of on-farm trials, new varieties of the crops were developed, which were adapted to Timor-Leste’s different production environments. Over the 16 years of the project, 19 improved varieties were released, and certified seed was provided to more than 65,000 farming families.

A significant legacy of the program was the establishment of a national seed-production system, which eliminated Timor-Leste’s longstanding dependency on imported seed. The seed-production system comprised both commercial and community-based seed producers, giving Timor-Leste the capacity to produce quality seed in response to farmer demands.

Mr Rob Williams, agriculture researcher based in Timor-Leste, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the University of Western Australia and a research leader with the Seeds of Life program, observed ongoing benefits.

‘Today [2022], around 75% of farmers in Timor-Leste use one or more of the crop varieties generated from Seeds of Life – this is up from 48% of farmers when the project concluded in 2016. In every village I’ve gone to in Timor-Leste, I’ve been able to find Seeds of Life sweetpotatoes growing which weren’t there before we started in 2000.

‘And now there are farmers who never used to sell sweetpotatoes, selling produce because they are growing sweetpotato varieties that yield twice as much in half the time. This supplies enough for their households plus extra to sell.’

A participatory research process based on genuine collaboration with farmers is identified as a key factor of success of the program. Between 2006 and 2015, Seeds of Life trained 2,600 people, including farmers, non-government organisation staff, employees from the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, and others. That way the local government had the capacity to continue to multiply and distribute seeds even after the project ended.

‘This approach has been embedded really well into the research department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. They know that having researchers who work with farmers as equals – testing things with the farmers, hearing the farmers’ feedback – is going to pay huge dividends in the future,’ said Mr Williams.

Building local expertise and careers

Embedded in many ACIAR-supported programs, and in step with the ACIAR mandate, is an element of capacity building. According to Dr Nesbitt, trained local personnel with the capacity to continue the research are key to a long-term legacy.

Over the 16 years of the Seeds of Life projects, many local researchers worked alongside Australian scientists. Seeds of Life helped to develop six functional agriculture research stations in Timor-Leste that continue to be heavily used by researchers funded by the Timor-Leste Government and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Seeds of Life sponsored 10 program staff to pursue master degrees, all of whom continue to work in agriculture or education in Timor-Leste. One staff member, Mr Luis de Almeida, went on to work on other ACIAR-supported projects when Seeds of Life concluded, including a project focused on agricultural innovation for farming communities in Timor-Leste.

‘Through Seeds of Life I learned research skills and connection with other partners as well as organisation and management skills, which I continue to apply to my work today.

‘I have a dream and a commitment to contribute to the agricultural development sector, which is vital for small and poor farmers in rural areas, especially in developing countries like my home, Timor-Leste.’

In May 2022, Mr de Almeida was appointed as the first ACIAR Country Manager for Timor-Leste. The Seeds of Life project continues to benefit participants – from the farmers who can grow better and more food, through to the research staff who received training and career opportunities.