- HomeHome

-

About ACIAR

- Our work

- Our people

-

Corporate information

- ACIAR Audit Committee

- Commission for International Agricultural Research

- Policy Advisory Council

- Agency reviews

- Executive remuneration disclosure

- Freedom of information (FOI)

- Gifts and benefits register

- Information publication scheme

- List of new agency files

- Contracts

- Legal services expenditure

- Privacy impact assessment register

- Commonwealth Child Safe Framework

- Benefits to Australia

- Careers

- 40 years of ACIAR

-

What we do

- Programs

- Cross-cutting areas

- Resources

- Where we work

-

Funding

- Research projects

- Fellowships

-

Scholarships

- John Allwright FellowshipScholarships to study in Australia for ACIAR partner country scientists to have Australian postgraduate qualifications

- ACIAR Pacific Agriculture Scholarships and Support and Climate Resilience Program

- Alumni Research Support Facility

- Publications

- News and Outreach

Date released

19 July 2019

ACIAR has been funding research in the Central Dry Zone of Myanmar, helping farmers grow more food in an increasingly challenging climate.

Food insecurity is a constant threat to the 12 million people living in the Central Dry Zone (CDZ) of Myanmar. The region's annual rainfall has halved since the 1950's and droughts are stretching for longer periods, making increasing crop productivity a major challenge for the smallholder farmers that call the region home.

With nearly half of the country’s pulse and oilseed legumes and three-quarters of sesame and sunflower produced in the CDZ, safeguarding the future of the region against an increasingly turbulent climate has been a priority for Myanmar’s Department of Agricultural Research (DAR).

In 2013, the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) with additional funding from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), supported the University of New England (UNE) to work with Myanmar’s DAR to increase productivity of legume-based farming systems.

Dubbed MyPulses, the project finished at the end of 2018, with a recently published final report detailing the long-term impact the project will have on agricultural production in the region, as well as contributing to the adoption of conservation farming principles in the CDZ and ensuring the long-term sustainability of cropping practices.

‘The soils of the central dry zone are very sandy, so they are quite drought prone,’ says Dr Robert Edis, then ACIAR Research Program Manager for Soil and Land Management. ‘They are also very low in nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur and a whole bunch of trace elements, so there’s a lot of opportunity to improve the fertility of soils in the region.’

The data collected by the team during the early stages of the project reinforced the challenge farmers in the CDZ are facing.

‘We look at statistical and climatic data, then paint a picture. We talk to the farmers who are telling us the rainfall is heavier when it comes, it’s coming less frequently which means the surface of the soil is drying out in between those big rainfall events, and it’s getting hotter.’ says Dr David Herridge, ACIAR project leader from UNE.

Developing new varieties

One of the main objectives of MyPulses was to develop new varieties of major food legumes. Pigeon pea, groundnut, chickpea, green gram and black gram have been grown to help bolster average crop yields against an increasingly warmer climate and improve resistance to pests and diseases.

‘One village in the CDZ might need a variety of legume that is highly tolerant to a soil-borne disease, another may need one that's very tolerant to dry conditions,’ says Dr Edis. ‘We’re giving farmers the confidence that the breeding programs and new legume varieties they’re getting will provide the effect they're looking for.’

A total of 54 researcher-managed trials took place during the five-year project. An additional 378 smaller trials were run by local farmers to test varieties sourced from the DAR and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) based in India.

To date, these trials have led to eight new varieties of legumes being developed, with two chickpea and two groundnut released throughout the project, with three pigeon pea and one groundnut variety due for release in 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

It’s in the bank

Developing new seed varieties, while increasing crop productivity, also posed a question of how best to disseminate the better performing varieties to farmers.

Dr Herridge said to solve this challenge they ‘set-up a concept called a Village Seed Bank. A little seed production unit within the village.’

The concept provided not only production of the new varieties, but also distribution of the higher-yielding seeds to farmers throughout the CDZ. During the project, 1592 seed banks were established giving an estimated 83,000 additional farmers access to the improved legume varieties.

The potential economic benefit of the new legume varieties being distributed via the village seed bank program was considerable, estimated at A$33million during 2015-18.

It's like a chain of trust embedded in a little seed.” – Dr Robert Edis

|

|

|

|

Fertiliser - Less more often

Engaging with farmers through MyPulses also changed the way they apply fertilisers. Before the arrival of the project team, farmers in the CDZ typically applied their fertiliser all at once. However, with increasingly erratic weather patterns and more intense rainfall events, single applications were often washed away leaving crops in need of vital nutrients.

Led by Dr Herridge, who has been conducting soil research on legumes in farming systems for almost 50 years, the UNE team worked with farmers to better understand the increasing impacts of climate—particularly rainfall—in nutrient leaching and the effect it has on crop productivity. The team emphasised to farmers the importance of split applications of fertiliser to ensure greater absorption by the plants.

‘We’ve introduced the concept of split applications,’ says Dr Herridge.‘We suggested farmers apply nutrients when planting, wait three weeks and apply some more, then wait another three weeks and apply a third load of nutrients. The best farmers that we work with are producing very good yields as a result.’

|

|

|

|

‘The farmers sowed traditionally before the project,’ says U Kyaw San, a pulse farmer in the CDZ who participated in the project.

'In the past, we just used the fertilisers that other people used. Since the project came, we can measure the soil pH. We know what level of pH is acidity, and I can use the fertiliser systematically. I also now know how to use N.P.K in ratio,’ he says.

These changes have also resulted in improved guidelines for rates and timing of inputs of farm-yard manure and mineral fertilisers for groundnut and sesame in the CDZ.

The introduction of split applications and providing farmers with the ability to measure soil pH levels for correct ratios of fertiliser nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium was all supported by the local DAR soil laboratory, which also greatly benefited from the MyPulses investment.

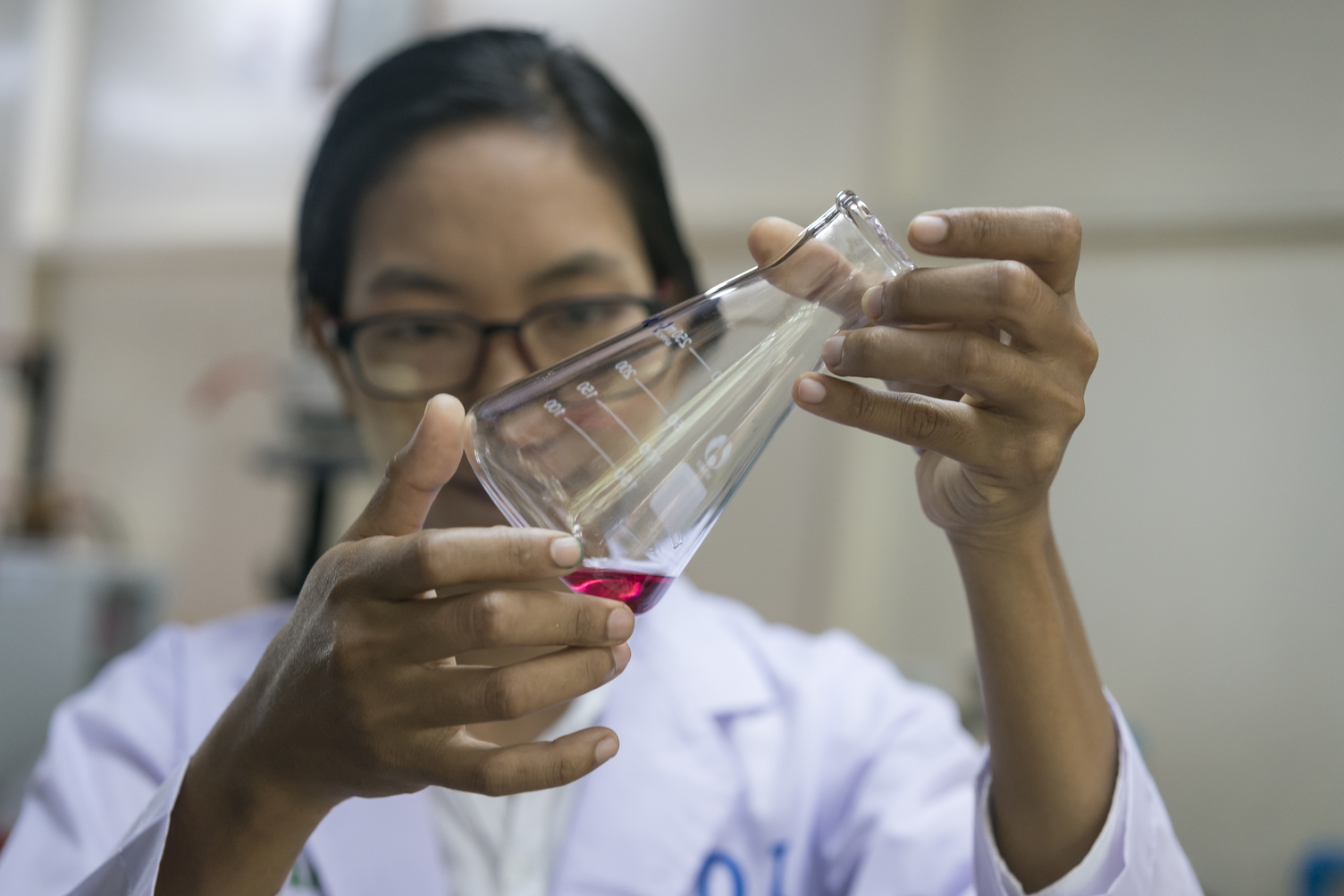

Growing research capacity in the lab

The DAR soil laboratory located in Naypyitaw played a vital role in the MyPulses project. It provided a valuable test facility for farmers that helped them understand and make management decisions related to the chemical composition of their soils and developed a decision support tool for nutrient management.

In the early days of the project, Dr Herridge foresaw the importance of the facility and implemented training initiatives to strengthen the skill and knowledge of the local soil scientists. Investment in infrastructure and equipment upgrades for the laboratory including a centrifuge, test tubes and racks, soil tumblers, bottle-top dispensers and pipettes, provided greater capacity and opportunity to conduct soil analysis.

These upgrades were supplemented by researchers from UNE delivering 86 days of on-site training to DAR scientists during the project, with two researchers attending short-term training in Australia, and another three undertaking postgraduate studies at UNE.

The additional training and equipment upgrades have significantly boosted the laboratory’s ability to work through large numbers of soil samples, substantially improving capacity for soil and plant analysis to underpin cropping in the CDZ.

|

|

|

|

‘This is the one and only research centre for agriculture in Myanmar,' says Dr Su Su Win, Director at the DAR Soil Laboratory who leads an all-female team. 'With 70% of our population working in farming, our work is very important to the country. The improvement in the lab's infrastructure means we can analyse more soil samples with greater accuracy and provide better suggestions to farmers on how they can improve their soil.'

When asked why Dr Su Su enjoys working on ACIAR projects she said ‘ACIAR teaches us how to catch the fish, rather than just giving us the fish—this is best aspect of working with ACIAR.'

The value of the unique approach ACIAR takes in being a long-term partner, rather than a short-term donor, is shared by Dr Herridge. ‘If you engage people as active collaborators, as active partners, then you go on the same journey. I think it’s the only way you can work,’ he says.

DAR and the farmers all work in soils, it’s their pallet, they grow things as if they were painting a picture,’ says Dr Edis. ‘They’ve built a reputation of being a good partner in research. The DAR Lab is certainly the best lab for soils, analysis and research in the region.

In addition to working closely with Dr Su Su Win’s team at the soil laboratory, the MyPulses project also undertook a total of 30 small capacity-building projects including 1 PhD and 6 MSc projects at Yezin Agricultural University involving 43 academics and students, a large majority of which were

A brighter future for the Central Dry Zone

Eight new varieties of drought and disease resistant legumes, the establishment of nearly 1,600 seed banks benefiting over 80,000 farmers, improved fertiliser and nutrient management practises and significant investments in developing Myanmar’s soil research capacity is the legacy of the MyPulses project.

The project’s final report, which can be found on ACIAR’s website, also calls for the broad adoption of conservation farming principles across the CDZ to further reduce the yield gap and ensure long-term sustainability of the cropping practices.

MyPulses was part of a wider effort by ACIAR to improve food security and farmer livelihoods in Myanmar, with four other projects—MyRice, MyFish, Dahat Pan and MyLife. All these initiatives apply technical, social and economic research to achieve practical impacts for Myanmar smallholders.