00:05

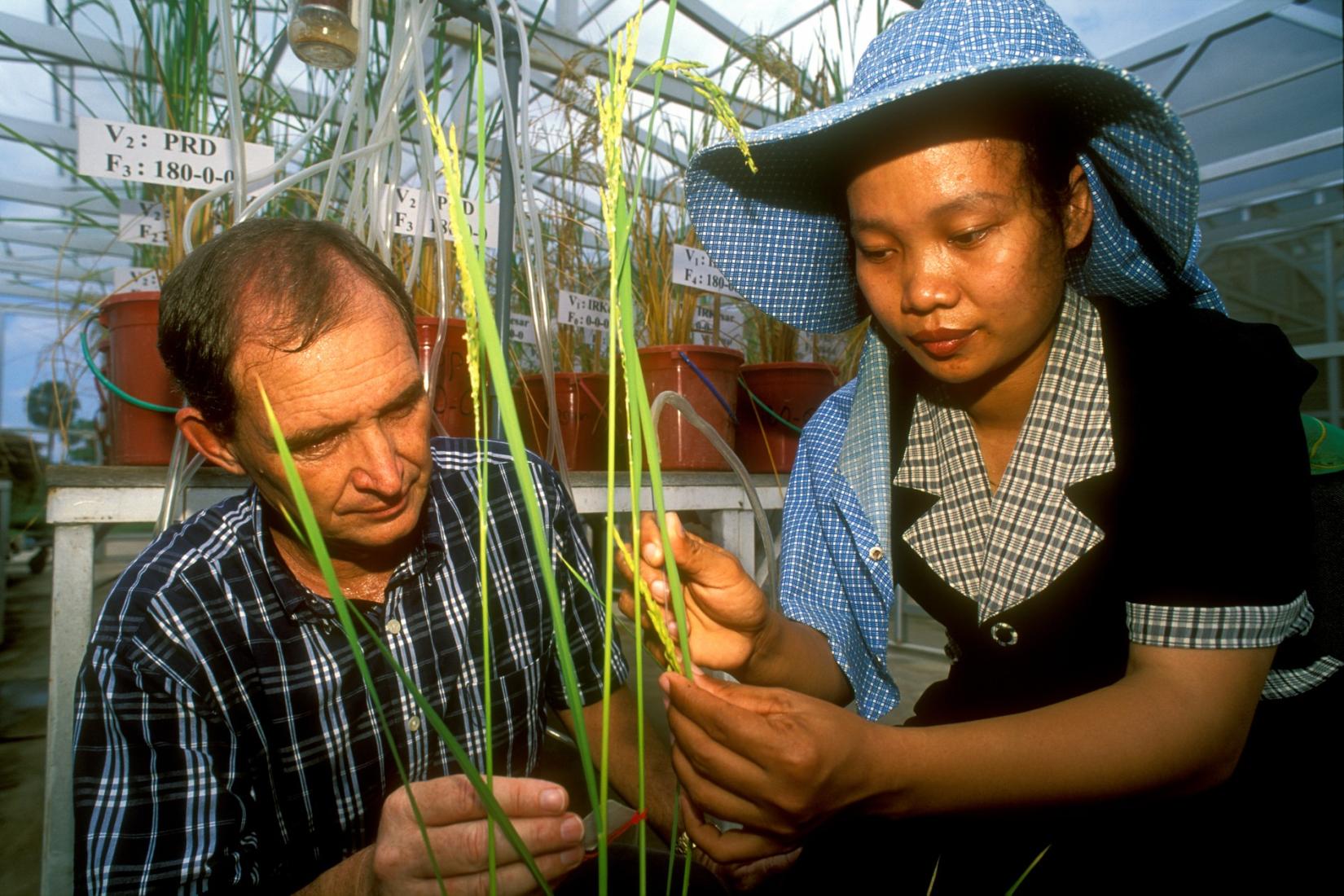

Host: Welcome to ACIAR Voices, stories from agricultural researchers and experts from across the world into the remarkable 40-year history of ACIAR, the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

00:26

Caroline: From Queensland sugar to African livestock and beyond, Gabrielle Persley has been at the forefront of international agricultural research and development for more than 30 years. Dr Persley’s distinguished career has taken her across the globe and into some of the world's leading agricultural and development agencies. But she was also there at the very start of what would become the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. And she has a few stories to share about how the organisation came to be and how critical it's been in her journey. Hello, I'm Caroline Winter and Dr Gabrielle Persley, thank you for joining me in the ACIAR studio.

01:04

Gabrielle: Thank you, Caroline. It's a pleasure to be here.

01:07

Caroline: You've had a distinguished career in international agricultural research and food security as a researcher and a Senior Science Leader at some of the world's leading agricultural and development agencies. How did this journey begin for you?

01:21

Gabrielle: Well, I guess my journey began, when I was studying, probably in high school when I decided that I wanted to be a scientist, and also that I wanted to use science to contribute to improving food and agriculture and health in the developing world. And so, I did science at the University of Queensland, when I graduated with a science degree, I then went to work with the Australian sugar industry. And I was with the sugar bureau for about five years, I spent a year in the UK as a rotary graduate fellow. And then I obtained a position in Nigeria, working as a pathologist on tropical plant diseases with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. So, my time in Nigeria, was when I got my first experience working in the developing world. And at that time, I then decided to come back to Australia, and to join the Australian overseas aid program, if that was possible, which is what I did. And that's how I got to Canberra and joined the then Australian Development Assistance Bureau, which led me into contributing to the creation of ACIAR.

02:44

Caroline: Now we've got a lot to talk about when it comes to ACIAR. I would like to take you back to that moment when you joined the Australian International Development Assistance Bureau. On reflection, how pivotal was that decision for you in your journey?

02:58

Gabrielle: Oh, it was an absolutely critical decision. Because in my time in Africa, I spent three years and travelled quite extensively throughout Africa with my research. But I came to the conclusion that if I wanted to make a difference, and to make this my long-term career in international agricultural development, then the best way to do that was to join a development assistance bureau. And that was a critical decision. And it was a conscious decision. It didn't happen by accident. So, I came back to Australia, after I'd finished my time in Africa, on that occasion, with the express intent of seeing how I went about joining the Australian Development Assistance Bureau.

03:47

Caroline: And obviously, from what came from that, over the years has shown how important that decision was for you and your career. It's taking you around the world from Washington, DC to West and East Africa, to The Hague, and Glasgow among other places. And over that time, you've forged strong links between Australian and international biotechnology, science and development communities. Is there a particular moment among all of that that stands out to you as being I guess, a highlight?

04:17

Gabrielle: That's an interesting question to try and think of one highlight over that time. But in many ways, the highlight and what started me on this road, which I couldn't envisage, when I first joined ADAB that somehow I did end up working for the World Bank in Washington, and I'd go back to Africa for another decade, etc. So I think being involved in the formation of ACIAR, was a critical moment and having the opportunity to work with people like Sir John Crawford and Mr. Jim Ingram, who is director of ADAB at the time, and Dennis Blight, all of whom became my long time and friends and colleagues that really set me on the path for the next four decades or more.

05:06

Caroline: So, let's talk about that time you were there at the inception of ACIAR. And before we explore that further, can you set the scene as to the cultural context at the time that sowed the seed for the organisation?

05:20

Gabrielle: Well, I think what was interesting, as I've been reflecting on that time of the late 70s, early 80s, there was a lot of North-South dialogue going on in various forums about what was needed to encourage the economic and social development of the countries in the south. And the Prime Minister of the day, Malcolm Fraser, was very engaged in these dialogues. And he saw that Australia had a unique role in that it was, to some extent, part of the so-called North in the terminology of the day, as an economically advanced country, but yet its geographic position in the south and its role in the Commonwealth gave it a very unique position. And what Prime Minister Fraser was doing through those years in supporting the Australian overseas aid program, encouraging new initiatives seeking engagement with the Australian research community, and the agricultural community was trying to position Australia as in some ways, a bridge between North and South. And I think that influenced the culture of the time and particularly the political culture, which made an agricultural research initiative fall on receptive grounds.

06:54

Caroline: So, it could have been in case of a well-timed idea presented to the right people at the right time. mentioning some of the gentleman you spoke about earlier for this to actually come about would that be right?

07:06

Gabrielle: Well indeed but this was a well-formed idea which took several years to formulate. And the political opportunity arose because the Australian Government was hosting the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting, which was to be held in Melbourne in October of 1981. And so that's why 1981 became a pivotal year because this idea of Australia doing more in the area of agricultural research had been discussed for a number of years, probably since, at least 1974, and Australia had been supporting bilateral projects before that through the aid program. But there was a view within the research community and the aid program that Australia could do more and could do more in a more systematic manner. And then the political opportunity arose, and the Prime Minister Fraser had been thinking very deeply in these areas. I was just reading the speech he gave to the Commonwealth Club in Adelaide in February 1981, which is a 10 page document and he goes through the economic, social, political environment, nothing and then Australia, but around the world and how we saw Australia's role moving forward, and was in that context that then he announced in Australia was contemplating a new agricultural research initiative.

08:40

Caroline: And there you were in Canberra with ADAB. So how did you become involved in the establishment of ACIAR?

08:47

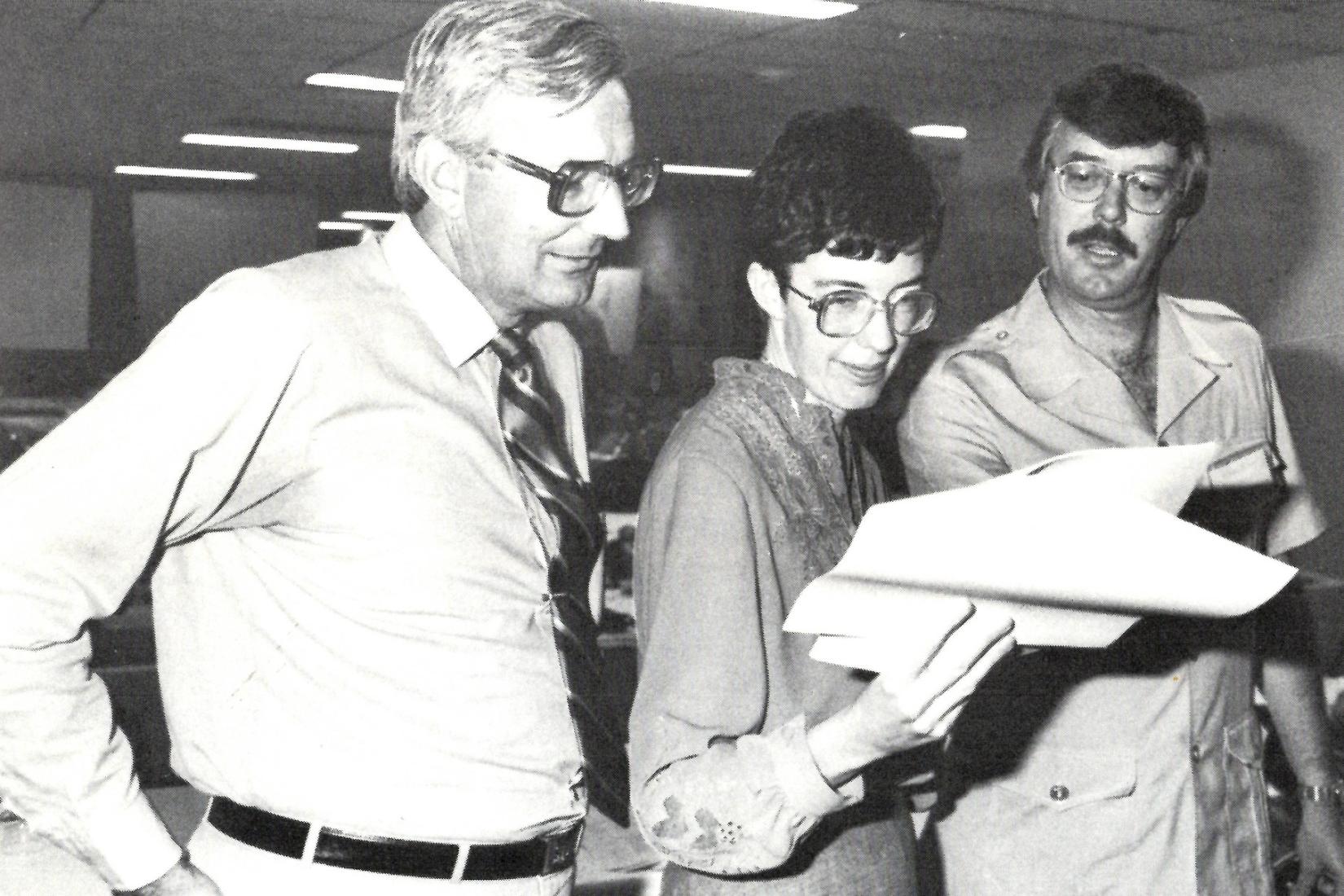

Gabrielle: It was fairly easy, because I was the only an agricultural research scientist in the building, and I'd been there for a year. And I'd been recruited by ADAB to join the then research for development unit. So, I had been working on some of the existing programs. So, when the initiative was being developed, and a task force was being formed within ADAB to develop this initiative fairly briskly, because the Prime Minister decided he’d like this initiative in January of 1981. That CHOGM meeting was going to be in October. So that basically gave nine months to get all this initiative together. So the small task force was formed, chaired by John Baker, and Mr. Ingram might seem to recall, call me up to his office and said, Gabriel, I'd like you to be on this task force to assist Dr. Baker. And I said certainly, Mr. Ingram. Thank you very much.

09:46

Caroline: And what were you feeling at that time you were right at the start of something that was new and innovative and exciting?

09:51

Gabrielle: Well, a combination of being really excited and fairly terrified about wondering how we'll do this, but let's carry on. John Baker. If it was a great person to work for, and Sir John Crawford was involved. And there was a committee within ADAB at the time called the Consultative Committee on research for development, which Sir John Crawford chaired, and had representatives from CSIRO, universities, and the State Department's of Agriculture. And so, I'd been part of the Secretariat of that committee for about a year. So, we knew the actors, and it was a great time because people like Jim Ingram and Sir John, simply expected you to get on and do whatever they asked you to do. And so, the only response was, yes, Sir John, go home and work all night and get it done.

10:43

Caroline: That sounds like quite a time and as you say, in a very condensed timeline to be ready for the launch, were there stressful moments, were their challenges, were there moments where it was all-nighters trying to put the final touches on this plan?

11:00

Gabrielle: There were several pivotal steps, because I think the January February period of 1981, that was when the Prime Minister was looking for an aid initiative to announce at CHOGM. Naturally, there are a few different groups around Canberra who had their own ideas on what that initiative should be. So therefore, those of us involved in developing the Agricultural Research Initiative, had to make sure the case was put very strongly. And of course, with Sir John Crawford, leading, putting the case, together with Jim Ingram, the director of ADAB. Then they could put a very strong case. And, as I've mentioned, this initiative had been several years in the making. So, it had been quite well fleshed out and thought through. So, getting the decision in mid-February, that yes, of the choices available, the Prime Minister and also the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Tony Street, at the time, they liked the idea of the Agricultural Research Initiative. And they felt this played to Australia's strength as a major agricultural exporting country, strong agricultural research community, and food being a central requirement in the developing world with agricultural growth, driving economic development. So, we have that very intense period through January/February of 81, in the next few months, from February through to July, was getting the cabinet submission prepared, because it's not the everybody in cabinet let alone everybody in the bureaucracy in Canberra, thought this was a great idea. This was the time also of the infamous razor gangs in Canberra, who were busy slashing departmental budgets and getting the cabinet submission together. And in fact, watching John Baker dealing with some of the other government departments who didn't like the idea of further aid initiative was very educational, I must say. But nevertheless, the Prime Minister was strongly behind this. And the cabinet agreed that this was a good initiative first and leadership role for Australia. And cabinet passed the submission in late July of 81 and committed $25 million over four years to establish ACIAR. That was a lot of money back then. Well, yes, it was a lot of money. And amongst a few documents, so I've been reading recently, there was an article that came out in the Sydney Morning Herald about the eighth of August of 81, and the headline says, PM’s project beats the razors.

13:55

Caroline: Testament to what you were saying just before about what was going on politically?

13:59

Gabrielle: Well, yes, exactly. And so now we've been engaged in conversations about the formation of ACIAR. And it can be simplified almost like, Well, this was a great idea. And everybody thought it was a great idea. And, and that's just how it started practically overnight. I'm thinking well, no, there was weeks, months of work, and lobbying and convincing financial Treasury that this was not about to break the bank, etc, etc. But I think it goes to show that when we have people like Sir John, Jim Ingram, all the others engage. And I think getting the engagement of the Australian agricultural research community, and the farming community was really important. The other thing that was important was making sure that there was bipartisan support. This concept of an agricultural research initiative was supported by both the major parties, so that was also helpful, particularly when it came to getting the legislation, through the parliament.

15:01

Caroline: Dr. Presley, you've talked a lot about Sir John Crawford. What was it like working alongside him? And do you have any memorable moments, I suppose, of doing this work with him in the lead up to ACIAR being established.

15:15

Gabrielle: Well Sir John was just a wonderful person to work with. And I think if many initiatives that sit on once engaged with everybody, who worked in these various different initiatives really valued, Sir John, and when you worked with Sir John, you had the feeling that you were the only group of people that he was really concerned with. You had his absolute full attention, and commitment. But then Denis Blight, I've often realised, that when the two of us were the first staff members of ACIAR, so there was Sir John, Denis as the the interim director, and there was me as the science advisor. And we knew that when he'd finished a meeting with us about ACIAR, then he'd go to another meeting, which might be about the Australia Japan Foundation, or who might be going to meet the Prime Minister to deal with trade and tariffs, etc. But everybody felt that Sir John was committed to your initiative, your work, and therefore, you tended to respond in kind to meet his expectations.

16:25

Caroline: There's some suggestion that it was you who drafted the first ACIAR act with Sir John, is that true? And what can you tell me about where and how that happened?

16:36

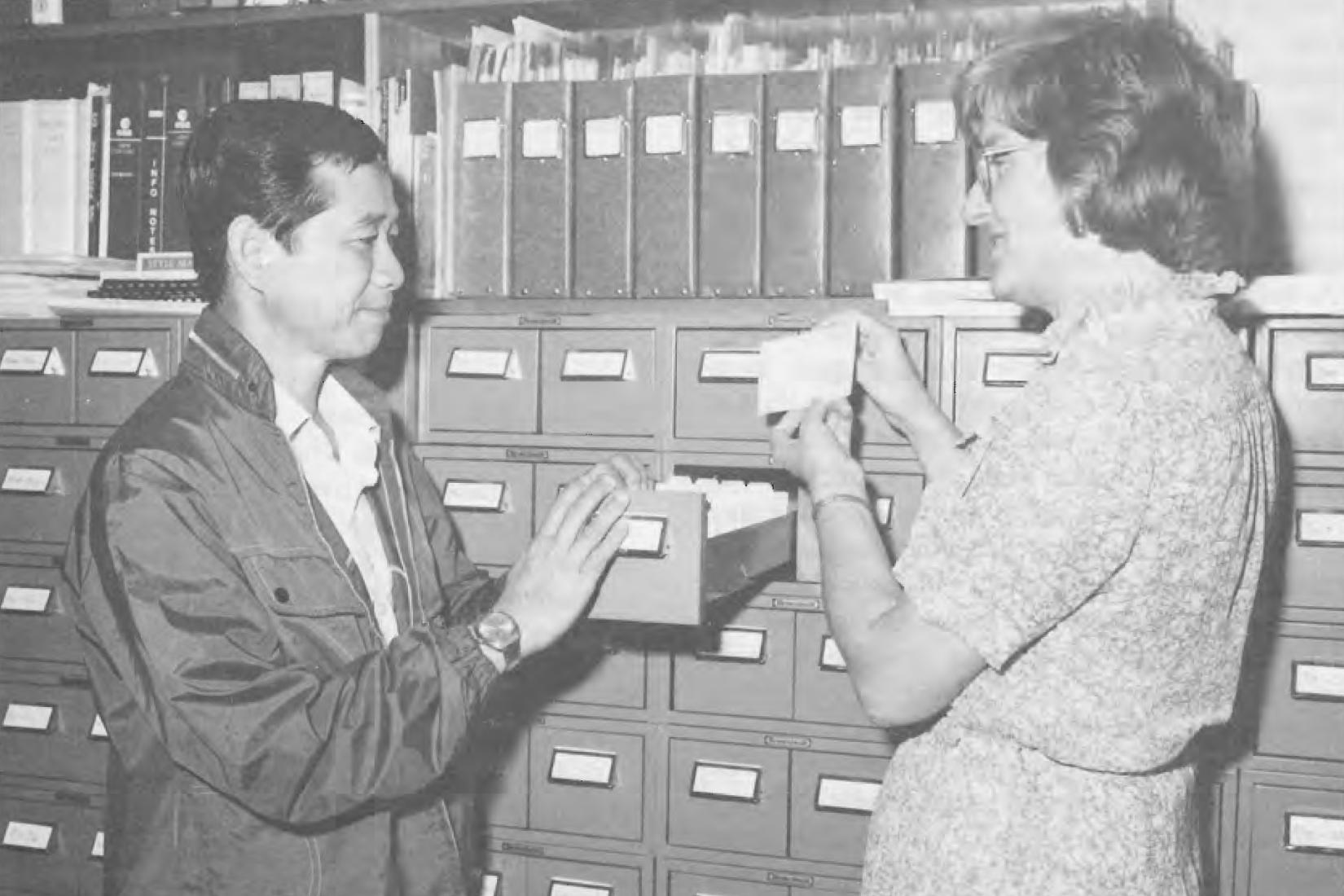

Gabrielle: Yes, to some degree, I would say that was true, at least in preparing a zero draft of the ACIAR act. How that came to be was that since I was a scientist, I had absolutely no idea how one might go about drafting legislation, obviously it had to do with seeking some appropriate help within Canberra. And I do recall very clearly calling in foreign affairs to ask well, how do I go about this? Who might I speak to who could draft an ACIAR act? He suggested I've called the parliamentary draftsman who suggested I call the attorney general's whatever. So, after several run around phone calls, I ended up back with the parliamentary draftsman saying, I really need some help here. We have this new organisation, we need legislation, what do you suggest, and he said, If I were you, I would call Miss Persley, in ACIAR, and she will be able to help you. And I said, thank you very much, and looked in the mirror and thought, well, I guess I better do something different. And so, I went down to the ADAB library went to see for Canada, because the Canadian government had established an International Development Research Center, and to some degree, ourselves has been modelled on IDRC. And Sir John, was the chair of the IDLC board. So, he knew a lot about IDRC. And, as luck would have it, the ADAB library had a copy of the Act, which established IDRC. So, I made a photocopy. I went back to my office with a pen and pencil, and worked my way through the IDRC act, relevant to the cabinet submission as to what were the purposes of ACIAR duly drafted this, then I've called the parliamentary draftsman back to say, Well, I'm Doctor Persley, I do have a zero draft of this act. Could I come and see you? And then you might be able to take it from there. And he said, certainly do come over. Because the draftsman has said, Well, I can't draft an act until you tell me what you want to do. So that that is an entirely true story. And I could tell you the conclusion of the story, you asked me for a milestone moment, which I do remember very clearly, because the Act went through the House of Representatives in October 81. And then it had to go through the Senate, which for various reasons, didn't happen until May of 82. And so, I was tasked to sit beside the Senator Margaret Guilfoyle, who was representing the Minister for Foreign Affairs in the Senate. So, I was to sit beside her on the Senate floor, and if there were any technical questions being asked to duly advise her i.e. write her a note. Anyway, that all went fairly smoothly. Although I must admit, I was quite terrified at the time thinking, I hope nobody asks anything too difficult here. But Margaret Guilfoyle was very pleasant. And then Senator John Button applied for the opposition also been very supportive, and the act was duly passed and I recall walking out of the Senate chamber, who did I run into, but Sir John Crawford, who had been up seeing the prime minister. And so, he sees me and says, Well Gabrielle, did it go through. I said, Yes, Sir John, he said, oh fine, we can get back to work now. See you tomorrow morning. Thank you, Sir John. And the Act was passed.

20:20

Caroline: So, you were field scientists turned researcher turned legislator in the end.

20:24

Gabrielle: Something like that. And I suppose I just, I just come back from spending three years in Nigeria and trekking around 22 countries in Africa. That was a pretty tough learning curve. So, somebody would like an act of fine. We'll go to the library and find one that suits and why don't we start from there.

20:43

Caroline: I know where to come when I need an act drawn up.

20:48

Gabrielle: Nobody will believe that story. But really, it is true.

20:52

Caroline: It's fabulous. I love it. Thank you for that. So, what was your role then within ACIAR once it was established.

20:59

Gabrielle: in June 82, when the act was proclaimed, so officially ACIAR started on the third of June 1982. And Denis Blight was appointed the interim director. So, John was appointed the Chairman of the Board of Management. And I was appointed as the Agricultural Research Advisor. And I was charged with developing the framework for the program. One of the first things that we did in that period was to organise, say, a series of consultations around Australia, about what should be the priorities framework. And in that, we were working with members of the Consultative Committee on research development, and particularly Dr. Ted Henzell, from CSIRO in Brisbane, he was chief of the CSIRO Division of Tropical Crops and Pastures. And so my role was to develop this priorities framework, which would then provide criteria against which the various projects been put forward from research scientists and research institutes in Australia and overseas, could then be considered and approved by the Board of Management. So, my role is through the rest of 82 was to help the first interim director, and then Jim McWilliam, came in as the first substantive director in August of 82. And so then, the three of us Denis, Jim and myself, worked very hard through that period to establish the program, of ACIAR. And then also additional research scientists who have been recruited to head up these different program areas in crops and animal sciences, soil sciences, forestry, post-harvest technology, and one or two others, but they were the initial programs, and then a short suite of projects came out of those areas.

22:53

Caroline: Fascinating. Dr Persley, without being presumptuous. This was the early 80s. And women in science and women in leadership roles were certainly not as commonplace as now. Your involvement in ACIAR was obviously more than right place and right time and clearly a reflection of your talent. Can you talk me through what that was like for you?

23:15

Gabrielle: Well, I never really paid much attention to tell you the truth. Because as I've mentioned in the introduction, I've tried graduated from the University of Queensland with my Bachelor of Science, I was employed by the Australian Sugar Industry. As a plant pathologist, I might say, I was the first woman graduate ever employed by the Sugar Bureau. And they'd been going for several decades. And so that was quite interesting, including when I first used to go out to the sugarcane farms to be looking at diseases, the farmers would look at me, because I was, in my early 20s, at the time, and the farmer would say, it really, it's too hot today. Why don't you just sit on the veranda with the missus and have a cup of tea? And the extension agent and I, will go and look at the sugarcane. And I’d just say, Oh, no, no, it's fine. I'll come with you. No problem. And then I went off to West Africa. And I was quite unusual in a way as a white woman running around the cassava farms of West Africa, but I never came to any difficulties whatsoever.

24:26

Caroline: That's lovely. So, there was that inclusion from the very start and not something that you obviously ever questioned or needed to question?

Gabrielle: No, no, not at all.

Caroline: Dr. Persley, your involvement in ACIAR has been long and fruitful. What has that involvement looked like over the four decades that the organisation has been going and more broadly in international agricultural research?

24:49

Gabrielle: Well, it's been quite an interesting evolution from my engagement with ACIAR in the early days and its formation. And then I spent several years as the research program manager for the crops program, but then towards the end of the 80s, new science was evolving very rapidly modern biosciences and genetic improvements with new technologies to speed up the rate been able to develop new crop varieties, for example, or modern vaccines or areas of animal health. And so, Jim McWilliam, suggested, well, I think it’d be a good idea if you went on sabbatical, and got up to speed on these, this new science and what it will mean for the developing world. And that was what led me to initially be working with the World Bank and one of the international agricultural research centres based in Europe, on looking at the role of new science, and how that would influence health and accelerate agricultural development. And so it was then leading me from ACIAR, to the World Bank, where I then joined the bank as the biotechnology advisor in the early 90s. And I stayed in Washington for about 10 years, working in various countries in supporting the development of research facilities and building capacity in areas of agricultural research. And through that period, I was, I was always in contact with ACIAR, not directly involved in the programs, but always looking for opportunities to partner, Australian scientists and scientist in the developing world. And then, after I finished with the World Bank, then I ended up back in Africa, particularly working in East Africa, on developing a shared biosciences platform, which was located at the International Livestock Research Institute. And that had support from several countries, including Canada, and the Syngenta Foundation, and also, Sweden, and Australia, and Western Australia, were developed a really good partnership with Australian scientists. In some ways, this was really mobilising what I'd learned in my time, and I see that money is one thing, but actually having really strong research collaborations with scientists from the partner country really is a big asset. And I think that partnership with Australian science and Becker that started in 2010 and went for several years from 2010 to 2016/17. That was a really strong and really great contribution from Australian science into Africa. And then after that, I completed a cycle and was invited to join the ACIAR commission in 2017.

27:55

Caroline: And that obviously brought you back to ACIAR. So, what has changed in how the organisation has approached its role in Australian international aid programs? How have you seen it change any milestone moments that were maybe pivotal in you recognising the change was happening?

28:11

Gabrielle: I think that's a really interesting consideration. Because, as I've been reflecting on this time, at the 40th anniversary, what I'm seeing is an interesting combination of the continuity, and the revitalisation, continuously reinventing ACIAR to fit the times. The thing that strikes me most in a way is that ACIAR has stayed true to the original objectives of basically supporting collaborative research projects between Australian and developing countries scientists on problems of mutual interest, and that has remained the driving force of the organisation. And secondly, actually, the continuous revitalisation has meant that ACIAR has expanded its scope of its programs. It's included more cross-cutting areas, in areas like gender and diversity, for example, in sustainable agriculture, in the role of agribusiness in agriculture. And in terms of pivotal moments. I think two pivotal moments have happened that over those 40 years, ACIAR has had six directors, and each of those have led the organisation extraordinarily well. And they've made the necessary changes in strategy or staffing or policy to fit the times. And so that has been really pivotal in having that strong leadership to steer the organisation through some uncharted territory and rocky periods, at certain times, particularly when there is a change of government? Because that's always a bit of a risk as well. And so there have been several changes of government and changes of Prime Minister, changes of ministers, and I think one thing that has stood ACIAR here in very good stead in periods of change is right from the beginning, very early on, and impact assessment unit was established under the leadership of Jim Ryan, a very well-known agricultural economist. So that meant that ACIAR was continuously evaluating itself, looking at what impact is this having, not only in the developing world, but also is it having positive impacts on Australian agriculture. So, there was an evidence base been built up to justify why this is a good investment of Australian aid money. So, there was this evidence. And then also the partnership model worked very well in the partner countries. And so ACIAR often didn't, usually didn't have as much money as a number of the larger countries, larger philanthropic organisations. But it bought the partnership with Australian scientists, which many other agencies did not. So that also meant that from a political perspective, for the Australian High Commissioners and the Australian Ambassadors and visiting ministers, they were always ACIAR projects doing good work, very well appreciated by the governments and countries as diverse as the Philippines and Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand. And this also meant there was evidence on the ground. Well, this is a small organisation relative to the overall size of the aid program, it's doing good work, it’s appreciated, carry on. So I think that it's not one pivotal moment, but it's it's an approach of continuity, focus, and continually reinventing the organisation to suit the times.

32:12

Caroline: Doctor Persley, you're back in your home state of Queensland. What are you doing now?

32:17

Gabrielle: Well, I was inadvertently detained here due to COVID. I was in working in Africa in February of 20. And working with some colleagues at the International Livestock Research Institute, and particularly on some animal health projects. So, I was sitting with my friends who are veterinary scientists and epidemiologists. And in February 20, we started looking at the John Hopkins maps of what’s this new disease? And where's it going? So, I recall very clearly one night sitting there looking at the maps and saying, Well, I guess I’m not staying here for the next few weeks. I think I'll be going home, preferably tomorrow. And one of my colleagues, he was planning to travel to South Korea, and then come on to Australia to developing some new animal health work together with some CSIRO scientists. So, I was saying to Edward, well, I guess you're not going to South Korea, nor, Australia just now. And he said, No, I guess not. I'll send them a video lecture instead. And that's just a little over two years ago. But I am planning to go back to Africa at some point. But I've been quite busy while I've been here. The University of Queensland very kindly welcomed me back to the School of Agriculture. So, I have an appointment as an honorary professor at the school. And I've been co-leading a project, which was also has been an operation in Africa, on-demand lead plant breeding. And this is a very interesting example of public-private sector, collaboration, and strongly supported by ACIAR, and the Syngenta foundation of for sustainable agriculture. And it's actually looking at ways to ensure that new crop varieties are meeting both farmer needs and market demands so that there is a high uptake of new varieties. And so I'm the co-leader of that project that's been in operation now for seven years. And now the end of the second phase, and we're transitioning to full African Leadership for the third phase. So that's been going very well. We have a community practice of 400 plant breeders who work in 30 countries across Africa. And this project develops professional development tools and opportunities to access new technologies for use in breeding programs. So that's been a major interest and my second interest which interestingly in 2017, some of my animal health colleagues, and a group I work with, in the Doyle Foundation and Scotland, where she held a meeting to discuss disease sentinels, and the role of animals in predicting and preventing future pandemics, which was fairly interesting. And so now we've hopefully survived the pandemic moving into the next phase of the pandemic. But regretfully, this will not be the last time that a disease jumps from an animal host into people. And this happens quite frequently. But not all of those incidences develop into a pandemic. And so the study I'm getting really heavily involved in now is, what can we understand about this both over time pre-COVID, but also now and COVID times? And what can be done in terms of what are the sentinels where early intervention can identify what pathogens have the potential to become pandemic? And most early interventions are possible to stop that outbreak developing into a pandemic? So that's a very timely study, I feel.

36:23

Caroline: Isn't it just some fascinating and exceptionally relevant work there that obviously you'll be continuing on? What do you see as the future opportunities for strengthening the impact of agricultural research worldwide?

36:37

Gabrielle: I think there's two areas here. One is to strengthen the capacity of researchers working on their own country's problems and developing solutions. And I think, over the past few decades that we're seeing countries have evolved in this regard. And particularly if I look at Southeast Asia, and the early raft of ACIAR projects, very strong within the ASEAN countries, Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, as examples, now a number of those countries have evolved to become major agricultural exporting countries, or economies have become Asian tigers. And if I use Thailand as an example, that now Thai scientists are participating in ACIAR projects in neighbouring countries, notably Cambodia, as an example. And students and scientists from those countries are studying at Thai universities. What I see as the future is increasing that in-country capacity and strengthening the institutions in country, particularly the universities, and the second area I see evolving is the role of the private sector, because delivery of new technology requires a functioning private sector in country. And particularly, maybe putting this as a third area, much more financing of agricultural research coming again, from the developing world, from individual countries, recognising that this is not a cost to their budget, that invest in agricultural research is an investment in their agricultural sector, which will give them a good return on that investment, and therefore less dependence on the international development community supporting relatively short term projects, and much more partnership models and much less investment from outside driving the research agenda in-country.

38:44

Caroline: There is much work to do you have absolutely played a big role in all of that. Doctor Persley, as we mark ACIAR 40th year, can you share with me a final thought on what the organisation means to you?

38:58

Gabrielle: I think I can look at ACIAR over those 40 years. And think well, that was for me personally, it was a wonderful opportunity, and set me off on my journey in international agricultural research. But it also led to a very large number of long-standing professional associations, people I've started working within the 80s I'm still working with today and different projects where we have mutual interests, and long-standing friendships as well, I think is so reflect on this and the years I've spent managing research programs and advocating investments in different programs. I've really come to the conclusion that basically people invest in people. Science is what I call a creative pursuit. It's undertaken by people, and therefore, it's really important when located anywhere particular area and including the projects in which ACIAR is invested. The whole critical exercise is to put the right partnerships together, put the right people together. I was discussing this with one of my friends recently, he sent me a nice little quote, which said, physics puts people together, and chemistry makes it work. I thought that's really nice. It's the chemistry that makes it work. And I think ACIAR has some pretty good chemistry. And that's really been a driving force.

40:34

Caroline: Dr Gabriel Persley, your insights and stories around ACIAR and agricultural research more broadly have been so enlightening. Thank you for joining me in the ACIAR studio.

40:43

Gabrielle: Thank you very much, Caroline.

40:47

Host: We hope you've enjoyed this episode of ACIAR voices in celebration of 40 years of ACIAR, listen to our other episodes to meet ACIAR luminaries and hear their stories of agricultural research for development from 1982 to 2022.