- HomeHome

-

About ACIAR

- Our work

- Our people

-

Corporate information

- ACIAR Audit Committee

- Commission for International Agricultural Research

- Policy Advisory Council

- Agency reviews

- Executive remuneration disclosure

- Freedom of information (FOI)

- Gifts and benefits register

- Information publication scheme

- List of new agency files

- Contracts

- Legal services expenditure

- Privacy impact assessment register

- Commonwealth Child Safe Framework

- Benefits to Australia

- Careers

- 40 years of ACIAR

-

What we do

- Programs

- Cross-cutting areas

- Resources

- Where we work

-

Funding

- Research projects

- Fellowships

-

Scholarships

- John Allwright FellowshipScholarships to study in Australia for ACIAR partner country scientists to have Australian postgraduate qualifications

- ACIAR Pacific Agriculture Scholarships and Support and Climate Resilience Program

- Alumni Research Support Facility

- Publications

- News and Outreach

Date released

16 December 2020

From combatting illegal logging to adding value to old coconut palms to support industry rejuvenation, ACIAR research is delivering innovative solutions to smallholder forest owners.

‘Biophysical and social innovation is critical to addressing challenges we face in creating, restoring, managing and protecting forest resources for human benefit,’ says Dr Nora Devoe, ACIAR Forestry Research Program Manager.

Two ACIAR projects show how forestry innovations can have an impact and support better environmental and economic outcomes.

The first is providing a way to track the origin of teak timber to ensure it comes from legal sources. The second is working with smallholder coconut farmers to process their old coconut trees for an economic return and as an incentive to renew their plantations with newer, healthier trees.

Teak ‘fingerprints’ thwart illegal trade

ACIAR research has successfully developed cost-effective DNA tests for one of the most valuable timbers in the world: teak. This brings authorities a step closer to shutting down the illegal trade in timber from South-East Asia and the Pacific region.

Samples of teak sent to the University of Adelaide were used to develop a DNA reference map of genetic variation for the valued species. Samples were sourced from natural forests in Myanmar, Laos and Thailand, and plantation teak forests in Laos and Indonesia. Work is underway to apply the same process in Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea.

Supporting sustainability

Completed in 2018 and on the back of two previous projects, an ACIAR small research activity aimed to reduce the trade in illegal timber for the economic benefit of producer countries and to improve the long-term sustainability of teak production.

Project leader, Professor Andrew Lowe from the University of Adelaide, says the DNA tracking will help to reduce the A$42.8 billion illicit trade of teak.

Verifying the paper trail

Project partner Double Helix Tracking Technologies, organised the sampling in Myanmar through local forestry partners and trained workers to take the tree samples and geo-reference each log.

Double Helix Chief Executive Officer, Mr Darren Thomas, says Myanmar foresters had very good forest management and paper documentation practices to authenticate the source of teak but the global movement of illegal timber made further assurance necessary.

‘One of the primary ways that illegal timber enters the market is through being mixed into legitimate supply chains, accompanied by fraudulent documents,’ Mr Thomas says.

‘Teak logs confiscated from illegal logging groups are resold into the market rather than destroyed so this has become controversial for customers in the European Union (EU), which requires illegal timber to be excluded from supply chains completely.

‘While mixing of legal and confiscated timber can be controlled in certified supply chains, the EU has raised doubts as to the reliability of paper verification.’

The DNA map shows at least five distinct genetic clusters for teak in Myanmar. Allowing for a 100 km tolerance, this DNA map accurately traced back 99% of blind-test samples to their claimed origin.

‘The Adelaide laboratory also applied DNA fingerprinting methods to match those blind samples of sawn timber from the log yard and cut tree stumps, and accurately traced each piece of timber to its individual tree stump in the forest or plantation,’ says Mr Thomas.

‘In Myanmar, forestry is an important source of foreign income, so this is a powerful means of restoring trust and confidence in the system.’

While DNA testing has become more cost-effective to support document verification audits, Mr Thomas says it’s not necessary to run tests on every shipment of timber.

‘For a consignment of sawn teak worth A$280,000 the DNA testing costs A$5,500 so it’s a case of figuring out how often that needs to be done and for what level of sales to sustain confidence in the system and encourage legal trade,’ he adds.

Results of the project were delivered at workshops in Indonesia, Myanmar, Solomon Islands and Laos, and training in field and laboratory procedures was provided to project partners from Indonesia, Laos, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Myanmar.

Extending the knowledge

Mr U Mehm Ko Ko Gyi from Myanmar’s Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative says while the DNA chain of custody will make a big difference to the local timber industry, more samples need to be collected and tested to extend the teak map across all parts of the country.

Professor Lowe says a follow-up study would also be useful to develop DNA testing methods for application in Myanmar laboratories with different technical capabilities.

This is a powerful means of restoring trust and confidence in the system.

Darren Thomas, Double Helix Tracking Technologies.

A DNA chain of custody system could also be designed to support a simplified, low-cost certification or third-party verification program to support smallholders’ sale of timber from community forests into higher-value markets.

In Indonesia, DNA was used to trace teak timber along a large plantation supply chain from the Perhutani Forest Management Unit at Cepu.

‘We trialled two methods that worked for large-scale industrial state-owned plantations in Indonesia—the first to check that logs at different points in the supply chain came from the same tree, which proved 90% accurate,’ Professor Lowe says.

‘The second tested whether logs matched the genetic profile of their source plantation and this was 100% accurate, and that’s what we recommend for large-scale and smallholder plantations.’

DNA tracking has previously been used in the USA to successfully prosecute the illegal trade in bigleaf maple. It is hoped this teak DNA map will be used in the same way to abolish illegally traded teak and support a sustainable teak supply chain.

Good wood from old, skinny coconuts

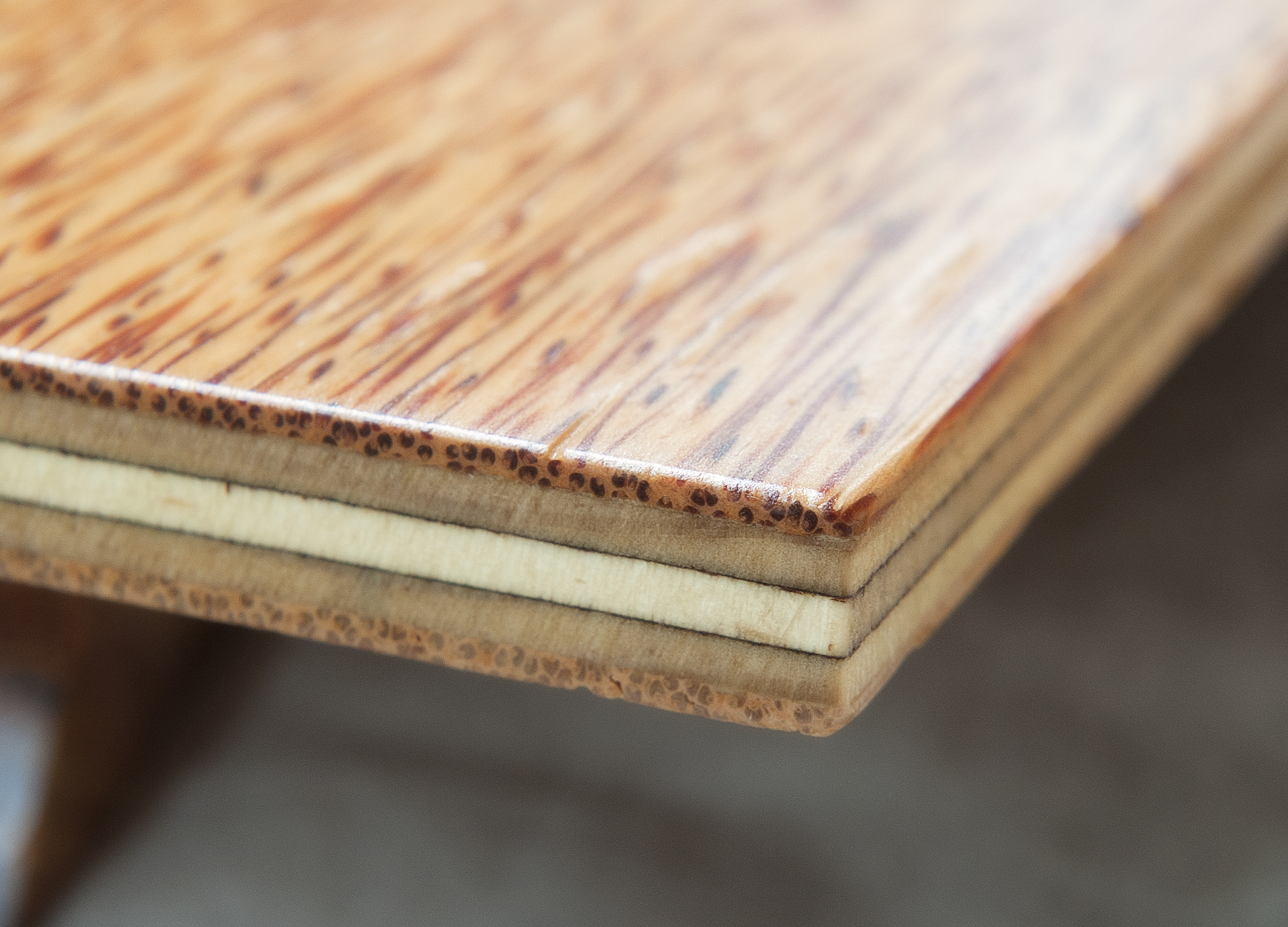

To produce wood veneer from old coconut palms and other small-diameter trees, a new ACIAR project is investigating the use of spindleless lathes. The technology has the potential to rejuvenate the timber industry in the Pacific region and provide farmers and forest owners with a new opportunity to gain value from trees that are often wasted.

The project will also provide owners of ageing coconut plantations with the incentive to replace their declining palms with new and better varieties. This can reduce pest and disease threats, increase yields and ensure a sustainable resource for the future.

Director for Timber Utilization and Research Division at Fiji’s Ministry of Forestry, Mr Tevita Bulai says that all parts of the coconut are useful, but senile coconuts older than 60 years are less productive. ‘They only produce 10 coconuts a year, or none at all,’ he says.

Coconuts are pivotal in the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in the Pacific region. Coconut consumption per capita averaged 2.84 kg worldwide in 2017, while in Fiji it was 61.2 kg. Coconut water and other coconut products such as copra and oil are key sources of income as well as nutrition. The palms also supply roof thatching, flooring and framing; materials for implements such as fish traps, baskets, and cordage; and shading for other food and cash crops.

Unsuited to traditional methods

The use of traditional wood sawing and processing systems to convert the stems of old coconut palms into high-value wood products for use in flooring and furniture has been largely unsuccessful due to the narrow trunks and composition of the plant.

Unlike trees which grow up and outwards, increasing their diameter and adding a new layer of wood each year, coconut palms grow upwards like grass and never achieve diameters above about 300 mm. This is a real challenge for traditional sawmilling and veneer processing equipment.

While the outside of a 60-year-old palm can be as dense as 1,000 kg/m3, the middle is a very soft 250 kg/m3.

Project leader Dr Rob McGavin, from Queensland’s Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (QDAF), says it is very difficult to recover the more attractive, higher density part of the log into sawn timber, with this part of the log often wasted in the conversion process.

Rotary peeling has the potential to recover this valuable part of the log, however traditional approaches use spindles to hold the centre of the log and rotate to allow the log to be unrolled. The problem is that these spindles just don’t work with the soft centre of coconut stems.

Spindleless lathes

Spindleless lathes have drive rollers that run on the log periphery for the length of the log and combine with a parallel blade to ‘unroll’ or peel it in a 3–5 mm sheet, leaving a residual core of about 40 mm.

‘This means we can recover around 70% of the stem from a senile coconut palm, compared to 20% or less using other options,’ says Dr McGavin.

‘The result is a high-quality veneer that can be used for the manufacture of structural and appearance engineered wood products.’

Other trees with small diameters, including those thinned from plantations, can be processed in the same way. This adds value and incentivises better forest management.

The five-year project is a partnership between ACIAR, QDAF, Fiji’s Ministry of Forestry and the Pacific Community (SPC). It also has four Australian forestry industry partners, including the Big River Group at Grafton, New South Wales. It builds on the work of two previous ACIAR projects with partners.

Beautiful and potentially valuable

Dr McGavin says coconut palm wood has a unique grain with a gold to dark-chocolate fleck. Coconut veneer or ‘cocoveneer’ is usually 3–6 mm thick and can be used in architecture, furniture and joinery, as well as structural plywood, packaging and high-quality laminated veneer lumber.

The direct return to farmers from the sale of senile coconut stems is expected to be small initially. However, once coconut-based engineered wood products are commercially produced, demand is expected to regularly supplement farm income within the economic haul distance of manufacturers.

The greater economic impact will be in the increased profitability of coconut-growing from renewing coconut stands with younger, more genetically diverse, resilient and productive coconut varieties. This will help improve the incomes of more than half a million households in the Pacific region that grow coconuts.

Growing from here

‘Spindleless lathes can be purchased for a fraction of the cost of traditional veneer lathes so this has great potential for widespread adoption in many developing countries,’ Dr McGavin says.

In Fiji there are already three registered veneer mills. The Ministry of Forestry wants to see collaboration between the industry and resource owners to process senile coconuts and other small-diameter logs into structural and engineered wood products.

‘We have enough capacity in terms of timber mills to process cocoveneer,’ says Mr Bulai. ‘I think this technology will mean an improvement in livelihoods especially for rural communities. The technology can be easily set up and easy to operate with less waste.’

There is also work to be done to build a skilled labour force to operate the lathes and develop cocoveneer markets. Dr McGavin also wants to better understand farmers’ perceptions about cutting down their oldest trees and waiting 6–7 years for new trees to fruit. Past incentive programs have encouraged farmers to replant with new and better varieties, but the success of many have been limited.

‘By providing a revenue stream for farmers through the sale of senile palm stems, this project will hopefully provide encouragement to remove older, less-productive stems and offset the costs of replanting,’ Dr McGavin says.

The project is scheduled to start before the end of 2020.

ACIAR Projects:

- Developing DNA-based chain of custody systems for legally-sourced teak, FST/2016/025

- Coconut and other non-traditional forest resources for the manufacture of engineered wood products, FST/2019/128

Key points

- Forestry innovations are helping smallholder farmers and forest-owners improve the sustainability and integrity of their enterprises.

- A new DNA map can be used to help verify the source of teak to help stamp out the illegal trade of the valuable timber and support legal smallholder trading.

- Processing coconut timber with a spindleless lathe could help incentivise farmers to replace their old coconut trees with new, healthier and more productive ones.