- HomeHome

-

About ACIAR

- Our work

- Our people

-

Corporate information

- ACIAR Audit Committee

- Commission for International Agricultural Research

- Policy Advisory Council

- Agency reviews

- Executive remuneration disclosure

- Freedom of information (FOI)

- Gifts and benefits register

- Information publication scheme

- List of new agency files

- Contracts

- Legal services expenditure

- Privacy impact assessment register

- Commonwealth Child Safe Framework

- Benefits to Australia

- Careers

- 40 years of ACIAR

-

What we do

- Programs

- Cross-cutting areas

- Resources

- Where we work

-

Funding

- Research projects

- Fellowships

-

Scholarships

- John Allwright FellowshipScholarships to study in Australia for ACIAR partner country scientists to have Australian postgraduate qualifications

- ACIAR Pacific Agriculture Scholarships and Support and Climate Resilience Program

- Alumni Research Support Facility

- Publications

- News and Outreach

Date released

04 April 2018

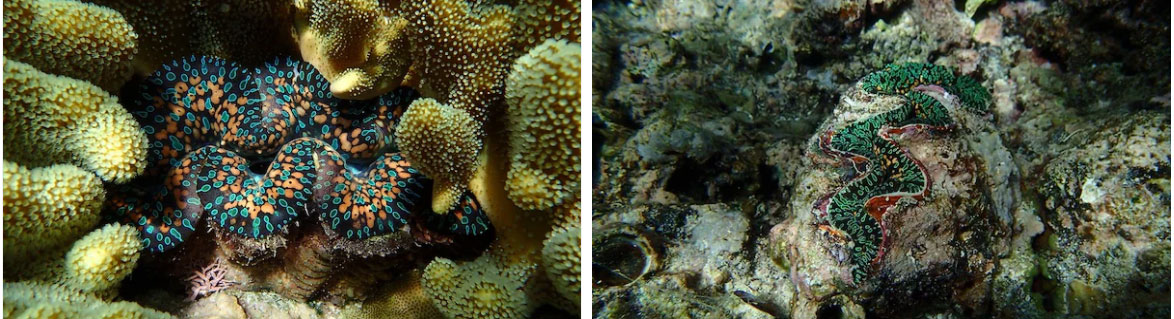

Professor Edgardo Gomez may not have single-handedly saved the ‘true giant clam’, Tridacna gigas, from extinction in the Philippines, but it certainly would not have happened without him. Returning from studies in the United States in the 1980s, he played a key role in one of ACIAR’s first projects, ‘The culture of the giant clam (Tridacna spp.) for food and restocking of reefs’, as Philippines project leader.

Today, there are estimated to be tens of thousands of giant clams on the reefs around the islands of the Philippines—an unmitigated success in terms of the project’s restocking objective. However, the giant clams are not there for food. Instead, and unforeseen by the original project planners, they are an increasingly valuable asset to a booming tourism sector, as well as a boost to reef health for fishing communities. “Things happened that we couldn’t have predicted at the start of the project,” explains Professor Gomez, who is in his 70s but no less committed to giant clams than he was 30 years ago. “We had to take a change of direction in 1996, when the Philippines government suddenly banned all giant clam exports.”

The early giant clam projects, which were also set up in Fiji, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Tonga, were a response to the drastic decline in giant clam populations across the Pacific caused by local overharvesting as well as poaching by foreign vessels. Research groups across the region joined forces to come up with the solution—an aquaculture system that linked giant clam breeding at national hatcheries with community farming of juvenile clams on the reefs, and ultimately with commercial markets that would provide economic sustainability and incentive.

Advancing giant clam science

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the projects were a great success in terms of scientific and technical advances. A series of ACIAR publications from 1992 chart the progress—The giant clam: an anatomical and histological atlas; The giant clam: a hatchery and nursery culture manual; The giant clam: an ocean culture manual; and Giant clams in the sustainable development of the South Pacific. But economic success proved more elusive. The story is slightly different in each project country, but in the Philippines the government decision in 1996 was a major setback to accessing the lucrative international aquarium trade.

“We had been focusing on Tridacna derasa up till then, as they were the most suitable for that market,” says Professor Gomez. “But at that point we decided to switch to gigas and to restocking the reefs around the country with this almostextinct species.” While the export ban may have been viewed as a setback at the time, today he sees it in quite a different light.

Then there was another lucky break for the project in the early 2000s when Professor Gomez was awarded a fellowship by the Pew Foundation, and with it a generous grant that he immediately deployed to assist the aquaculture and restocking program. By 2006 he was able to publish impressive numbers in an article ‘Achievements and lessons learned in restocking giant clams in the Philippines’—more than 70,000 giant clams restored to the reefs around the country by the aquaculture program.

Today, both the restocking program and giant clam-related research continue at the University of the Philippines’ Bolinao Marine Laboratory. Young giant clams continue to be in high demand across the country, and the laboratory runs regular training courses so that community members and resort staff know how to care for the juveniles when they receive them from the hatchery. As well as being a tourist drawcard, community interest in restoring giant clams to their reefs is high—coastal communities attest to a healthier marine ecosystem where giant clams are living, and they are careful to protect their restocked giant clams from poachers.

Healthy coastal fisheries

How does ACIAR view its investment in giant clams, three decades later? Dr Chris Barlow, former fisheries research program manager, says much has changed in the research approach, and today the focus would probably not be on a single species or group but on the broader ecosystem within a community-based fisheries management approach. Nonetheless, he says: “We are seeing some very interesting outcomes. Communities are telling us that giant clams mean healthy coastal fisheries, so they have a role that wasn’t anticipated as indicator species within successful community-managed marine areas.” And he points out that without the aquaculture projects, these animals—which also have immense cultural value across the Pacific—would likely have been lost to communities, surviving only as rare exhibits in highly protected areas.

In the Philippines, the project helped lay the groundwork for one of the leading centres for coral reef research in the Pacific region, the University of the Philippines’ Marine Science Institute and its Marine Laboratory at Bolinao. A new generation of marine biologists, taught and mentored by Professor Gomez, are entering a new phase of research. Dr Patrick Cabaitan and Dr Cecilia Conaco recently published evidence of natural breeding of the restocked T. gigas, a breakthrough in itself but also, it is hoped, paving the way for new and exciting research on ocean circulation models based on movement of the giant clam larvae.

The best learning often comes from unanticipated results, and ACIAR is keen to better understand the outcomes of the giant clam projects. An impact study has been released, unpicking the complexities of the projects and identifying lessons that could improve the research system.

This article was originally published in Partners Magazine, Issue Three, 2017.